You Play the Girl by Carina Chocano

Subtitle: On Playboy Bunnies, Princesses, Trainwrecks & Other Manmade Women

Other editions subtitle: On Playboy Bunnies, Stepford Wives, Trainwrecks & Other Mixed Messages

Other editions subtitle: and Other Vexing Stories That Tell Women Who They Are

Carina Chocono was losing her mind as a movie critic:

Carina Chocono was losing her mind as a movie critic:

“I found myself spending hours in the dark, consuming toxic doses of superhero movies, wedding-themed romance comedies, cryptofascist paeans to war, and bromances about unattractive, immature young men and the gorgeous women desperate to marry them. Hardly any movies had female protagonists. Most actresses were cast to play ‘the girl’.”

Chocono credits film actor Isla Fisher with slapping her awake. Asked whether her break-out success in The Wedding Crashers opened opportunities for her, Fisher had reportedly replied, “All the scripts are for men and you play ‘the girl’ in the hot rod.”

As Chocono noted, “Women’s experience in its entirety seemed contained in that remark, not to mention several of the stages of feminist grief: the shock of waking up to the fact that the world does not also belong to you; the shame at having been so naïve as to have thought it did; the indignation, depression, and despair that follow this realization; and, finally, the marshaling of the handy coping mechanisms, compartmentalization, pragmatism, and diminished expectations.”

As Chocono noted, “Women’s experience in its entirety seemed contained in that remark, not to mention several of the stages of feminist grief: the shock of waking up to the fact that the world does not also belong to you; the shame at having been so naïve as to have thought it did; the indignation, depression, and despair that follow this realization; and, finally, the marshaling of the handy coping mechanisms, compartmentalization, pragmatism, and diminished expectations.”

Before diminishing into being a “movie” critic, Chocono had thought of herself as a “film” critic (her distinction): “I wrote about what interested me and reacted to whatever seemed to be worth reacting to in the moment.” She used film as the springboard to freeform meditations on issues that resonated – as Renata Adler wrote, writing “about an event, about anything”, “putting films idiosyncratically alongside things [writers] cared about in other ways”.

You Play The Girl is a collection of essays Carina Chocono has written utilising Adler’s approach: responses to film as “a way into larger cultural conversations”.

It’s also – which cannot surprise anyone who’s read my previous blogs exploring approaches to writing memoir – a memoir, of sorts.

Finely etched as a filigree narrative spanning these essays is the story of how Carina Chocono figured out how to save her marriage (Chapter 2 Can This Marriage Be Saved?), be a good mother, be a good writer, and find her way back onto the heroine’s path:

Finely etched as a filigree narrative spanning these essays is the story of how Carina Chocono figured out how to save her marriage (Chapter 2 Can This Marriage Be Saved?), be a good mother, be a good writer, and find her way back onto the heroine’s path:

“The heroine’s journey starts with the realization that she is trapped inside the illusion of a perfect world where she has no power. She employs coping strategies at first, or tries to deny reality, but eventually she is betrayed, or loses everything, and can no longer lie to herself. She wakes up. She gathers her courage. She finds her willingness to go it alone. She faces her own symbolic death. […] The heroine’s journey is circular. It moves forward in spirals and burrows inward, to understanding. […] The path is treacherous. The territory is hostile. But the heroine is brave. She knows what she wants. She’s determined to get it. Isn’t that how all good stories start?”

Yes but. As Herr Freud asked, “What do women want?”

For Chocono, it’s autonomy, agency, and authority. Also, equity and self-expression. To love and to be loved.

For Chocono, it’s autonomy, agency, and authority. Also, equity and self-expression. To love and to be loved.

This book is dedicated to the author’s primary school aged daughter, from “For Kira” on the dedication page to the penultimate thank you in the Acknowledgements: “And to my amazing daughter, Kira, for being ever curious, always insisting on presenting her evidence, and never holding her tongue.”

The ultimate acknowledgement goes to one of Chocono’s heroines: “And to Hillary Clinton, for inspiring us both.”

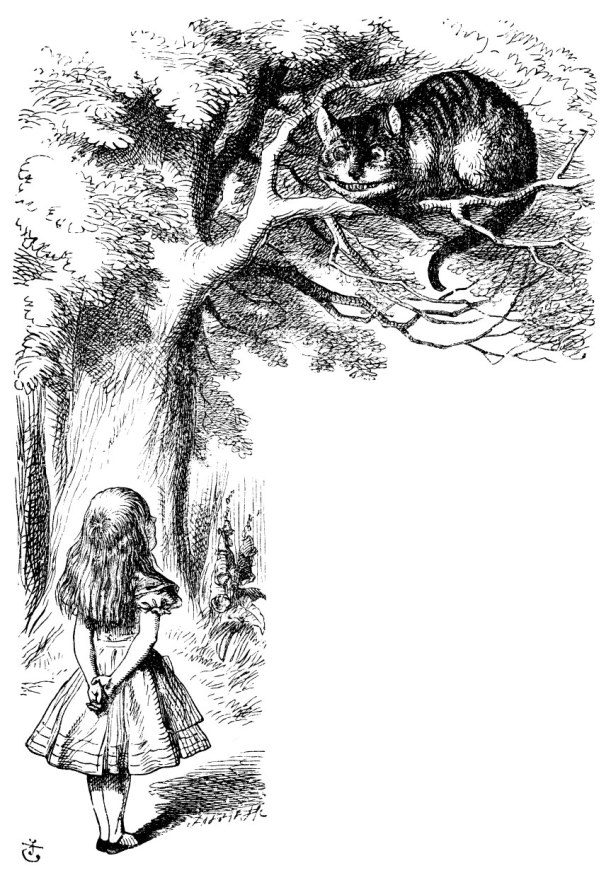

The memoir elements tracing Chocono’s marriage are subtle, and tender, but Chocono repeatedly refers back to cultural texts that provide explicit metaphors: Lewis Carroll’s mad worlds, Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass; the folk tales and fairy tales of Hans Christian Anderson, the Brothers Grimm and Charles Perrault; and the ways those folkloric tales have been reconfigured by Disney, Pixar and Hollywood more generally.

For me, Chocono is at her best deconstructing the Princess in popular culture, as she does in the chapter ‘All The Bad Guys Are Girls’. Her princesses range widely: encompassing Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty/Aurora, Elsa and Anna, and Maleficent; but also Edith Wharton’s Lily Bart, Katharine Hepburn as Tracy Lord, and Betty Draper from Mad Men. She re-presents the Jennifer Beals character in Flashdance and the Julia Roberts character in Pretty Woman as “princesses’, based on their exceptionalism. (She savages both films, hilariously.)

She asks her daughter ‘What is a princess, anyway?’

Kira replies, “It’s a very fancy woman who gets her own way.”

What most horrifies Chocono though is what happens after the ‘happy ever after’. As she points out (and as I discuss in previous blogs), a medieval princess knew she was simply a transmitter of bloodlines and a vehicle for political alliances: her role was to get up the aisle with as little fuss as possible, pop out some heirs, and remain ‘invisible’ as an individual, whether alive or dead. Even in more recent times, for girls born into elites within stratified societies (as Chocono’s great-grandmother was, in Peru), ”A woman’s education was designed to coax her to sleep at sixteen and keep her unchanged and unconscious forever. It was an undoing. It wasn’t a start but a ‘finishing’.”

Elsewhere, in her synopsis of the film Maleficent, Chicano describes the narrative building from when “King Stefan’s men try to kill Maleficent, and Aurora tries to help her and discovers [Maleficent’s hacked off] wings in a glass case, because everybody is putting girls and their parts in glass cases all the time in these stories…”

These prince “heroes” in Frozen and Maleficent are sociopaths who mutilate and usurp women with extraordinary gifts. They’re Buffalo Bill in The Silence of The Lambs appropriating women’s skin. They’re monsters.

Yet in popular culture, just as often, what women see reflected back is the princess as monster. To quote David Bowie, ‘I looked around / and the monster was me’.

There’s a chapter called ‘Bunnies’ that I thought might be about the Bunny Boilers, but it is in fact about lads’ mags and the Playboy magazine ideal. Bunny Boilers surface instead in the chapter titled ‘The Eternal Allure of the Basket Case’. The Basket Case makes reference to Virginia Woolf (who Chocono cites frequently), and to artists’ muses, including Courtney Love, with a glancing mention of Zelda Fitzgerald but in-depth focus on Isabelle Adjani’s most famous studies in madness, in the films The Story of Adele H and Camille Claudel. Sylvia Plath pops up. Girl, Interrupted and Fatal Attraction are the Hollywood texts, along with an HBO show I haven’t seen, Enlightened, where Laura Dern loses her mind then loses her job. Or, arguably, the other way round.

Reading Chocono’s analysis of Adele H, I was reminded of when I first read reviews of this film, when it was released, in 1975, when I was 14. Director Francois Truffaut based his film on a real life story. Adele was the daughter of French literary titan Victor Hugo, writer of the novel Les Miserables. A young English army lieutenant had proposed to Adele, but she turned him down. Later, she regretted doing so, and, uninvited, followed his regiment to Canada, where she stalked him for years, then followed his regiment to Barbados, where eventually one day he confronted her, only for it to be apparent she did not recognise him.

Adele is a princess, daughter of the greatest French literary hero of the nineteenth-century. She is a Romantic: Chocono quotes philosopher Isaiah Berlin’s definition of Romanticism as “the unappeasable yearning for unattainable goals”. She quotes from Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s book The Madwoman In The Attic, a study of “madness as feminist protest, subversion, and resistance. The madwoman, they say, serves as ‘the author’s double, and image of her own anxiety and rage’ towards a culture that oppresses her.”

Is Adele’s madness also her own misplaced sense of entitlement? Is she being a “princess”, a “very fancy woman” who thinks she can get her own way by ‘virtue’ of her privilege and passion? Is she on the “heroine’s journey”?

Virtue, as Mae West almost said but didn’t, has nothing to do with it.

Reading again about Adele H reminded me of two vintage Hollywood films that made an impact on me when I was 12, both about mad and bad bunny boilers who selfishly insisted on loving men who did not want to be loved (by them). I was so distressed by these two films that I wrote about them at length in my then-diary. I have long since burnt those diaries. But I think I remember what I had to say.

The first film was Forever Amber (1947), starring Cornel Wilde, the Texan actress Linda Darnell, and George Sanders as King Charles II. Amber is a luscious 16 year old country girl when Wilde, playing randy cavalier (a tautology?) Lord Bruce Carlton, age 29 when our story starts, rapes her as he’s en route to London. Except it isn’t really rape because obviously she was too luscious to remain virgin and was gagging for it anyway, and because she falls Wilde-ly in love with Bruce and hitches a ride with him to the metropolis. Amber remains ardently in love with Bruce Carlton even as she sleeps her way to being the king’s mistress. She nurses Bruce when he collapses with plague. She lances his pustules. She lends him money and advocates on his behalf. In return, he scorns her as a fallen woman, derides her as shallow and selfish, and eventually, once he marries a demure young heiress, he takes the child Amber bore to him away to the colony of Virginia, away from the child’s whore mother, away from the contaminated royal court.

I felt that was unfair. Amber didn’t get to experience much love. She loved her son. Bruce was, reductively, a prick. She did not deserve his bad treatment of her.

It did not occur to me at age 12 that Amber might be capable of recognising all this herself and washing her hands of the bastard.

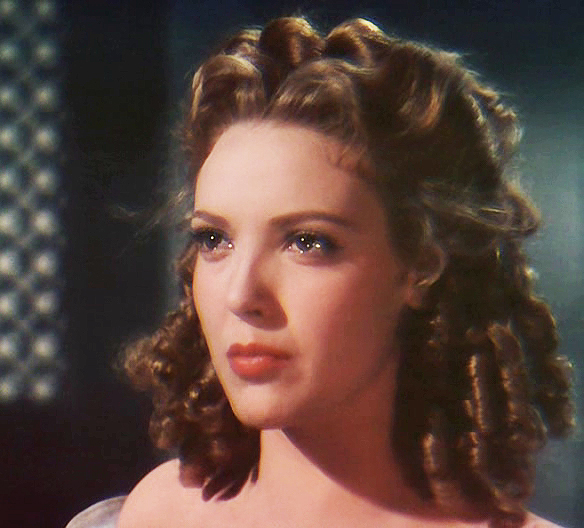

The second film was Leave Her to Heaven (1945), starring Gene Tierney and, again, Cornel Wilde, this time playing a writer who meets a beautiful woman, Ellen, on a train en route to her father’s funeral: the beautiful woman is especially emotionally vulnerable. Or out and out psycho. After their whirlwind marriage her obsessive jealousy and, yes, selfishness emerge. The writer has a disabled younger brother who comes to live with them. Bunny Boiler Ellen can’t bear to share her husband’s love so she watches, cold-bloodedly, as the boy drowns in a boating incident. Then her husband the writer finds solace in his friendship with her half-sister. He even dedicates his new novel to the sister, as “The gal with the hoe”. (She gardens.) Or was that dedication to “The gal with the hole”? Or “the gal with the ho’”?

Whatever. The Bunny Boiler had my sympathies.

Ellen flings her pregnant self down the stairs, cruelly murdering the writer’s innocent unborn son. When he walks out on her, she kills herself, setting up her sister and her husband for a murder charge. Knowing what we know about partner violence, it would be more credible if the writer had killed the Bunny Boiler, as Michael Douglas eventually kills Alex Forrest in Fatal Attraction (but she was asking for it). The screen-writer does kill Gene Tierney’s character. But only after he first assassinates it.

To me, this, too, did not seem fair. Granted, Ellen was intense. She failed to sufficiently empathise with her husband’s needs. But all she asked was to be loved.

To me, this, too, did not seem fair. Granted, Ellen was intense. She failed to sufficiently empathise with her husband’s needs. But all she asked was to be loved.

Gene Tierney’s problem was that she was a princess. She was a very fancy, over-entitled daddy’s girl who thought the world – or if not the whole world, her husband, at least – should love her unconditionally.

The Gene Tierney character is the Wicked Witch. She failed to play ‘the Girl’ the way ‘the Girl’ should be played – in the passenger seat.

To return to Isla Fisher: “All the scripts are for men and you play ‘the girl’ in the hot rod”:

“Women’s experience in its entirety seemed contained in that remark, not to mention several of the stages of feminist grief: the shock of waking up to the fact that the world does not also belong to you; the shame at having been so naïve as to have thought it did; the indignation, depression, and despair that follow this realization; and, finally, the marshaling of the handy coping mechanisms, compartmentalization, pragmatism, and diminished expectations.”

Or, the alternative coping mechanisms of madness and murder.

“’The girl’ doesn’t act, though – she behaves. She has no cause, but a plight. She doesn’t want anything, she is wanted.” For every princess who transforms into a witch, goes murderously crazy, there’s another – many others – being gaslighted: manipulated into believing, as Carina Chocono did, that she is losing her mind.

From Alice In Wonderland:

“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.”

“How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice.

“You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here.”