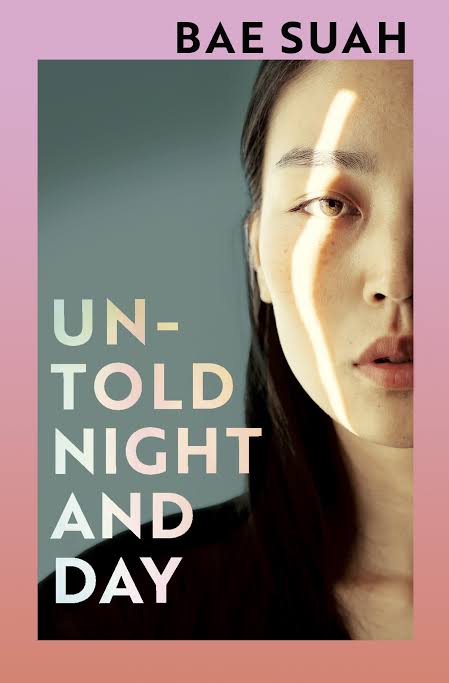

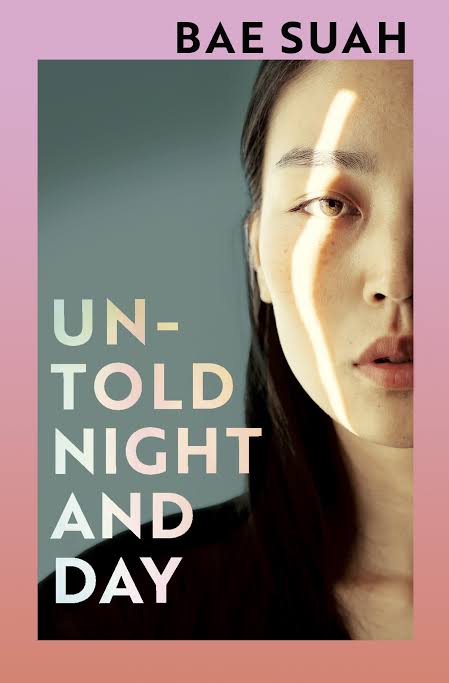

I knew nothing about this novel when I opened the first page and for much of the following 152 pages I still felt I knew almost nothing.

Yet when I finished page 152 I was in love with this text. I kept reading and re-reading the final pages. I didn’t want it to end.

I read Untold Night and Day in 50 page chunks (yes, I’m obsessed with the numbers). To me it reads like a prose poem, so 50 pages was as much as I could take in at a time.

After the first 50 pages, I read Deborah Smith’s Translator’s Notes, at the end, which I found helpful:

Bae’s oppositions are emphatically not binaries. Her books are filled with repetition, mirroring, echoing, overlapping […] Simultaneously is another thread-word studding the text.

Many years ago, when I was a poet, an editor described my poems as “games of rhythm and repetition”, which was apt. I came to enjoy the circularity of Bae’s world in Untold Night and Day, and the chunks of repetition.

The quotes on the book jacket are similarly apt:

“As cryptic and compelling as a fever dream […] a vivid and disorientating exploration of identity, artifice and compulsion” – Sharlene Tao

“I loved its uncanny beauty, its startling occurrences. As it unravels you feel […] yourself unravelling too” – Daisy Johnson

“Haunting and poetic […] holds the reader in a suspended state, allowing us to explore the tension of the threshold” – Chloe Aridjis

Untold Night and Day is filled with oppressive heat and damp, small concrete rooms, dank alleys, circling traffic, recurrences, identity switches, blocks to communication, temporal distortions…

Very early on, I recognised the figure of a girl in a coarse white hanbok (traditional dress), wearing woven hemp sandals, with her hair tied back in a low pony-tail, as a figure from the Korean spirit world: the young girl ghost, or supernatural entity.

The main female character is called Ayami (and sometimes other names). Bae has explained that “According to Siberian shamanism [the forebear of Korean shamanism], ayami is the name for the spirit that enters the shaman’s body and communicates matters of the other world to them.”

But Deborah Smith rightly points out that Untold Night and Day does not proclaim or labor its “Koreanness”. She quotes the self-mocking Korean joke rejecting Other-ing: “Oh, let me go put on some hanbok.”

So it’s contemporary experimental literary writing, rather than a hanbok tale.

What strikes me, reading during COVID-19 uncertainty and a wave of job losses and business failures, is that the narrative commences with two central characters being made redundant.

Ayami could be a spirit guide escorting a man to another world. Or they could both be casualties, on a more mundane level:

“Ayami [comforted him] for a long time, as though the repetitive gesture might conjure a shamanic power – the only way of keeping together, in the same place and time, two human beings in the process of disintegrating.”