I find myself unable to work with WordPress Block editing. Apologies to the poets whose poems are not set out as they should be here.

Lee Herrick

Flight

The in-flight magazine crossword partially done,

a corner begun here, scratched out answers there,

one set of answers in pencil, another in the green.

The woman with the green ball point knew

the all-time hit king is Rose and the Siem Reap

treasure is Angkor Wat. The woman, perhaps en route

to hold her dying mother’s hand in Seattle, forgot

about death for ten minutes while remembering her

husband’s Cincinnati Reds hat while gardening after

the diagnosis. Her handwriting was so clean. Maybe

she was a surgeon. Maybe a painter. No. What painter

wouldn’t know 17 down, Diego’s love, five letters?

In a rush, her dying mother’s voice came back

to her, or maybe she was Chinese and her mother’s

imagined voice said, wo ai ni. At 30,000 feet,

you focus on 33 across, Asian American classic,

The Woman ________, when a stranger in the window

seat sees the clue, watches me write in W, and she says

Warrior, and for a moment you forget it is your favorite

memoir, and she reminds you of lilies or roses, Van Gogh

or stems with thorns, art galleries in romantic cities

where she is headed but you should not go. The flight

attendant grazes my shoulder. The crossword squares,

the letters, the chairs and aisles seem so tight in flight,

but there is nothing here but room, really.

Maybe the next passenger will know

what I do not: 64 down, five letters, Purpose.

And why do we remember what we do? We know

the buzz of Dickinson’s fly and the number of years

in Marquez’s solitude, but some things we will never

know, as it should be: why the body sometimes rumbles

like a plane hurtling over southern Oregon, how exactly

we fall in love, or if Frida and Maxine Hong

Kingston would have loved the same kind of tea.

Originally published in Daily Gramma, October 2016.

The Birds Outside My Window Sing During a Pandemic

What we need has always been inside of us.

For some—a few poets or farmers, perhaps—

it’s always near the surface. Others, it’s buried.

It was in our original design, though—pre-machine,

pre-border, pre-pandemic. I imagine it like the light

one might feel through the body before dying,

a warm calm, a slow breath, a sweet rush.

There is, by every measure, reason for fear,

concern, a concert in the balcony of anxiety

made of what has also always been inside of us:

a kind of knowing that everything could break.

But it hasn’t quite yet and probably won’t.

What I mean to say is, I had a daydream

and got lost inside of it. There were dozens

of birds for some reason, who sounded like

they were singing in different accents:

shelter in place, shelter in place.

You’re made of stars and grace.

Stars and grace. Stars—and grace.

Originally published in MiGoZine, March 2020.

∞

Burlee Vang

To Live in the Zombie Apocalypse

The moon will shine for God

knows how long.

As if it still matters. As if someone

is trying to recall a dream.

Believe the brain is a cage of light

& rage. When it shuts off,

something else switches on.

There’s no better reason than now

to lock the doors, the windows.

Turn off the sprinklers

& porch light. Save the books

for fire. In darkness,

we learn to read

what moves along the horizon,

across the periphery of a gun scope—

the flicker of shadows,

the rustling of trash in the body

of cities long emptied.

Not a soul lives

in this house &

this house & this

house. Go on, stiffen

the heart, quicken

the blood. To live

in a world of flesh

& teeth, you must

learn to kill

what you love,

& love what can die.

Copyright © 2016 by Burlee Vang. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on December 20, 2016, by the Academy of American Poets.

∞

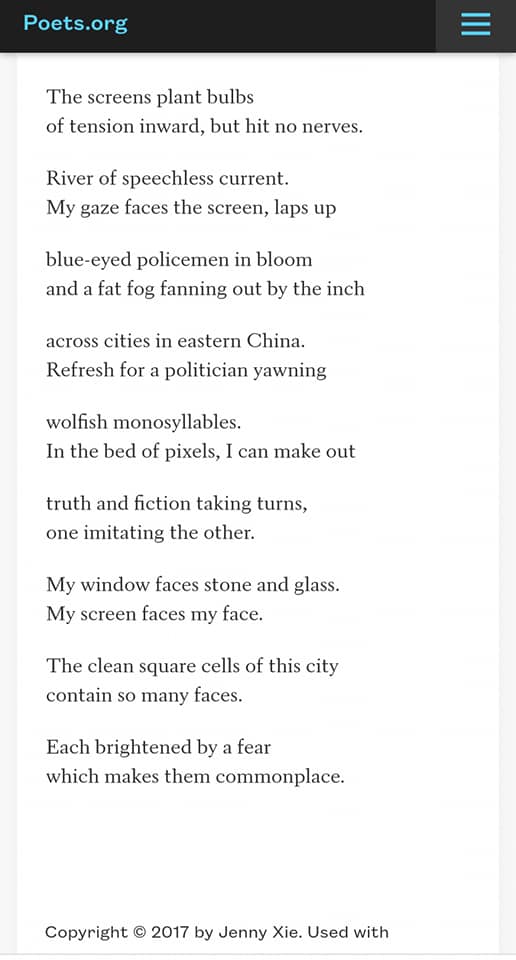

Jenny Xie

Square Cells

The screens plant bulbs

of tension inward, but hit no nerves.

River of speechless current.

My gaze faces the screen, laps up

blue-eyed policemen in bloom

and a fat fog fanning out by the inch

across cities in eastern China.

Refresh for a politician yawning

wolfish monosyllables.

In the bed of pixels, I can make out

truth and fiction taking turns,

one imitating the other.

My window faces stone and glass.

My screen faces my face.

The clean square cells of this city

contain so many faces.

Each brightened by a fear

which makes them commonplace.

Copyright © 2017 by Jenny Xie.

e.e. cummings

Amores (I)

your little voice

Over the wires came leaping

and i felt suddenly

dizzy

With the jostling and shouting of merry flowers

wee skipping high-heeled flames

courtesied before my eyes

or twinkling over to my side

Looked up

with impertinently exquisite faces

floating hands were laid upon me

I was whirled and tossed into delicious dancing

up

Up

with the pale important

stars and the Humorous

moon

dear girl

How i was crazy how i cried when i heard

over time

and tide and death

leaping

Sweetly

your voice

Jane Hirshfield

Like Others

In the end,

I was like others.

A person.

Sometimes embarrassed,

sometimes afraid.

When “Fire!” was shouted,

some ran toward it,

some away—

I neck-deep among them.

—2017

Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Recipe For Happiness Khaborovsk Or Anyplace

“Poetry is a naked woman, a naked man, and the distance between them.”

One grand boulevard with trees

with one grand cafe in sun

with strong black coffee in very small cups.

One not necessarily very beautiful

man or woman who loves you.

One fine day.

Alexandra Teague

Adjectives of Order

That summer, she had a student who was obsessed with the order of adjectives. A soldier in the South Vietnamese army, he had been taken prisoner when Saigon fell. He wanted to know why the order could not be altered. The sweltering city streets shook with rockets and helicopters. The city sweltering streets. On the dusty brown field of the chalkboard, she wrote: The mother took warm homemade bread from the oven. City is essential to streets as homemade is essential to bread . He copied this down, but he wanted to know if his brothers were lost before older, if he worked security at a twenty-story modern downtown bank or downtown twenty-story modern. When he first arrived, he did not know enough English to order a sandwich. He asked her to explain each part of Lovely big rectangular old red English Catholic leather Bible. Evaluation before size. Age before color. Nationality before religion. Time before length. Adding and, one could determine if two adjectives were equal. After Saigon fell, he had survived nine long years of torture. Nine and long. He knew no other way to say this.

From Mortal Geography by Alexandra Teague, Persea Books. Copyright © 2010 by Alexandra Teague.

Alexandra Teague

Late American Aubade

Man in a chicken suit, you’re the only one today

not selling beauty: 5th Avenue star-struck with Christmas,

three-story diamonds and flocks of ballerinas pirouetting

clockworking gears as if the Industrial Revolution

were a life-sized music box of desires and we’ve just kept

on winding. If. And Wish Upon. And shopping bag. And you

with your wind-ruffled feathers and flyers, pleading

for our primitive hungers. That inelegant grease spot

and crunch to remind us. The mannequins don’t

even have bones. I’ll never have a purse nice enough

to hold a wallet worth the money to buy the purse

at Barney’s. And what does it matter? There are drumsticks.

I’m a vegetarian. You are no masked creature worth hugging

for a picture. No Minnie. No marble nymph of Beauty

in pigeon net outside the library: old yet ever new eternal voice

and inward word. As if we hear it clear in the gizzard:

Beauty is God and love made real. You will be this beautiful

if. You are the rock in the crowd-raked garden of traffic,

just past the corner of jaguar-made-of-dazzle and flapper

reading Shakespeare bound in bardic sparkles. Your yellow,

a scant flag to claim us: ordinary strange as holy chickens

in a gilded cage in Spain. Their ancestors, heralds

of a miracle. A huge mechanical owl recites Madonna

in a window Baz Luhrmann designed since February.

It takes all year for a miracle with this many moving parts.

All of us in a rush to wait for the catastrophe of personality

to seem beautiful again. As if this is the best we can hope for:

seeming to ourselves—like panhandlers dressed as Buddhist

monks the real monks are protesting. Asked for her secret, the model for Beauty said, The dimples on my back

have been more valuable to me than war bonds. Asked for proof,

one orange-robed woman said, I can’t tell you where, but I do

have a temple. Beaked promise of later lunch, catastrophe

of unbeautiful feather, how can we eat the real you

that you are not? Which came first? The shell to hatch

desire, or desire? Which skin holds my glittering temple?

Copyright © 2016 by Alexandra Teague. “Late American Aubade” originally appeared in Cimarron Review.

Yi Lei

A Single Woman’s Bedroom

translated by Tracy K. Smith & Changtai Bi

1. Mirror Trick

Of course you know her.

She is one and many,

A multitude flashing on, then off,

Watching out from the tidy blank

of her face. She is silent, speaking

With just her mind. She is flesh, a form,

but also flat, a mute screen.

What she offers you, by no means

Should you accept. She belongs to no-one,

sitting like a ghost beyond her own reach.

And yet, she’s there—I mean me—

Behind glass, as if the world has been cleaved,

Though something whole remains,

Roving, free, a voice with poise and pitch.

She’s there—me—snug in the glass,

The little mirror on the bedside

Doing its one trick

A hundred times a day.

You didn’t come to live with me.

2. Turkish Bath

The room is choked with nudes.

Once, a man tried to muscle in by mistake

Crying, “Turkish bath!” He had no idea

My door is always locked in this heat,

No idea that I am the sole guest and client,

The chief consort, that I cast my gaze

Of pity and absolute pride across

The length of my limbs—lithe, pristine—

The bells of my breasts singing,

The high bright note of my ass,

My shoulders a warm chord,

The chorus of muscle that rings

Ecstatic. I am my own model.

I create, am created, my bed

Is heaped with photo albums,

Socks and slips scatted on a table.

A spray of winter jasmine wilts

In its glass vase, dim yellow, like

Despondent gold. Blossoms carpet

The floor, which is a patchwork

Of pillows. Pick a corner, sleep in peace.

You didn’t come to live with me.

3. Curtain Habit

The curtain seals out the day.

Better that way to let my mind

See what it sees (every evil under the sun),

Or to kneel before the heart, quiet king,

Feeling brave and consummately free.

Better that way to let all that I want

And all I believe swarm me like bees,

Or ghosts, or a cloud of smoke someone

Blows, beckoning. I come. I cry out

In release. I give birth

To a battery of clever babies—triplets,

Quintuplets, so many all at once.

The curtain seals in my joy.

The curtain holds the razor out of reach,

Puts the pills on a shelf out of sight.

The curtain snuffs shut and I bask in the bounty

Of being alive. The music begins.

Love pools in every corner.

You didn’t come to live with me.

4. Self-Portrait

The camera snaps. Spits me out starkly ugly.

So I set out to paint the self within myself.

It takes twelve tubes, blended to a living tint,

Before I believe me. I name the mixture Color P.

The hair—curious, unlikely—is my favorite,

The same fluff of bangs tickling my niece’s face.

And my eyebrows are wide as hills. They swallow everything.

They are a feat. They do not impress me as likely to age.

They are brimming with wisdom. Neither slavish nor stern.

Not magnificent, but not the kind made to crumple in shame.

Not prudish. Unwilling to arch and beckon like a whore’s.

They skitter away from certainties like alive or dead.

My self-portrait hangs on the narrow wall,

And I kneel down to it every day.

You didn’t come to live with me.

5. Impromptu Party

The little table is draped with a festive cloth, and

Light blurs out from a single lamp, making us fuzzy.

A sip of red wine, and I rise to my feet. We are

Dancing, my guests and I, like kids in a ballroom.

We don’t smile or even speak.

We’ve had a lot to drink.

To a single woman, time is like a scrap of meat:

Nothing you can afford to give away. I want

To hold it in my lap, Time, that sneak, that thief already

Scheming to break free. Please—I beg

Upon the magnificent extravagance of my beloved stilettos,

I want the world back. I’ve been alive—could it be?—

Near a century. My face has closed up shop.

My feet are a desolate country.

For a single woman, youth is a feast that lasts

Only until it is gone.

You didn’t come to live with me.

6. Invitation

When it arrived, I was interrupted by relief,

Sitting in my rattan chair, feeling the wind ease in

Through the hole in my life.

I only said yes because of his dissertation. Friends,

Nothing more. We talked—he talked—about modernism,

Black humor. But always at a distance from reality.

Why didn’t he ask me anything?

Tender and petulant, he struck me as cute.

But at heart, only a very well-behaved boy.

He offers his arm. Elegant, decent, gallant.

But how can I prove myself a woman

If he is a child? What can come of that union?

Can any of us save ourselves? Save another?

You didn’t come to live with me.

7. Sunday Alone

I don’t picnic on Sundays.

Parks are a sad song; I steer clear.

But I dug out all my sheet music,

I lolled about in the Turkish Bath

Singing from breakfast to tea.

With my hair, I sang Do

And my eyes, Re

And my ear sounded Mi

And my nose went after Fa

My face tilted back and out rose So

My mouth breathed La

My whole body birthed Ti

Like my cousin said, famously—

Music is the soul sighing.

Music pushes back against pain.

Solitude is great (but I don’t want

Greatness). My eyes slump

Against the walls. My hair

Hurls itself at the ceiling like a colony

Of bats.

You didn’t come to live with me.

8. Dialectic

I read materialist philosophy—

Material ispeerless.

But I’m creationless.

I don’t even procreate.

What use does the world have for me

Here beside my reams of cock-eyed drafts

That nick away at the mountain of

Art and philosophy?

Firstly, Existentialism.

Secondly, Dadaism.

Thirdly, Positivism.

Lastly, Surrealism.

Mostly, I think people live

For the sake of living.

Is living a feat?

What will last?

My chief function is obsolescence.

Still, I send out my stubborn breath

In every direction. I am determined

To commit myself to a marriage

Of connivance.

You didn’t come to live with me.

9. Downpour

Rain hacks at the earth like an insatiable man.

Disquiet, like passion, subsides instantly.

Six distinct desires mate, are later married.

At the moment, I want everything and nothing.

The rainstorm barricaded all the roads. Sandbags.

Isn’t there something gladdening about a dead-end?

I canceled my plans, my trysts, my escapes.

For a moment—I almost blinked and missed it—the storm

Stopped the clock that chases me. The clock of the heart, maybe.

It was an ecstasy so profound…

“Ah, linger on, thou art so fair!”

I’d rather admit despair. And die.

You didn’t come to live with me.

10. Dream of Symbolism

I occupy the walls that surround me.

When did I become so rectilinear?

I had a rectilinear dream:

The rectilinear sky in Leo:

The head, for a while, shone brightest.

Next the tail. After a while

It became a wild horse

Galloping into the distances of the universe,

Lasso dragging behind, tethered to nothing.

There are no roads in the black night that contains us.

Every step is a step into absence.

I don’t remember the last time I saw

A free soul. If she still exists, fire-eyed gypsy,

She’ll die young.

You didn’t come to live with me.

11. Birthday Candles

They are like heaps of stars.

My flat roof is like a private galaxy

That stretches on stubbornly forever.

The universe created us by chance,

Our birth, simple happenstance.

Should life be guarded or gambled?

Lodged in a vault or flung to the wind?

God announces: Happy Birthday.

Everyone raises a glass and giggles audibly.

Death gets clearer in the distance. Closer by a year.

Because all are afraid, none is afraid.

It’s pity how fast youth sputters and burns,

Its flame like the season’s last peony.

A bright misery.

You didn’t come to live with me.

12. Cigarette

I lift it to my lips, supremely slim,

Igniting my desire to be a woman.

I appreciate the grace of the gesture,

Cosmopolitan, a shorthand for beauty,

The winding haze off the tip like the chaos of sex.

Loneliness can be sweet. I re-read the paper.

The ban on smoking underway

Has gotten a bonfire of support. A heated topic,

Though I find it inflammatory. Authority

Flings a struck match in our direction, then

Gasps when we flare into flame. Law:

A contest between low-lives and sophisticates,

Though only time knows who is who.

Tonight I want to commit a victimless crime.

You didn’t come to live with me.

13. Thinking

I spend all my spare time doing it.

I give it a name: walking indoors.

I imagine a life in which I possess

All that I lack. I fix what has failed.

What never was, I build and seize.

It’s impossible to think of everything,

Yet more and more I do. Thinking

What I am afraid to say keeps fear

And fear’s twin, rage, at bay. Law

Squints out from its burrow, jams

Its quiver with arrows. It shoots

Like it thinks: never straight. My thoughts

Escape. One day, they’ll emigrate

To a kingdom far-off and heady.

My visa’s in-process, though like anyone,

I worry it’s overpopulated already.

You didn’t come to live with me.

14. Hope

This city of riches has fallen empty.

Small rooms like mine are easy to breech.

Watchmen pace, peer in, gazes hungry.

I come and go, always alone, heavy with worry.

My flesh forsakes itself. Strangers’ eyes

Drill into me till I bleed. I beg God:

Make me a ghost. Something invisible

Blocks every road. I wait night after night

With a hope beyond hope. If you come,

Will nation rise against nation? If you come,

Will the Yellow River drown its banks?

If you come, will the sky blacken and rage?

Will your coming decimate the harvest?

There is nothing I can do in the face of all I hate.

What I hate most is the person I’ve become.

You didn’t come to live with me.

Copyright © 2018 by Tracy K. Smith.

Thich Nhat Hanh

Please Call Me by My True Names

Don’t say that I will depart tomorrow —even today I am still arriving.

Look deeply: every second I am arriving to be a bud on a Spring branch, to be a tiny bird, with still-fragile wings, learning to sing in my new nest, to be a caterpillar in the heart of a flower, to be a jewel hiding itself in a stone.

I still arrive, in order to laugh and to cry, to fear and to hope. The rhythm of my heart is the birth and death of all that is alive.

I am the mayfly metamorphosing on the surface of the river. And I am the bird that swoops down to swallow the mayfly.

I am the frog swimming happily in the clear water of a pond. And I am the grass-snake that silently feeds itself on the frog.

I am the child in Uganda, all skin and bones, my legs as thin as bamboo sticks. And I am the arms merchant, selling deadly weapons to Uganda.

I am the twelve-year-old girl, refugee on a small boat, who throws herself into the ocean after being raped by a sea pirate.

And I am the pirate, my heart not yet capable of seeing and loving.

I am a member of the politburo, with plenty of power in my hands. And I am the man who has to pay his “debt of blood” to my people dying slowly in a forced-labor camp.

My joy is like Spring, so warm it makes flowers bloom all over the Earth. My pain is like a river of tears, so vast it fills the four oceans.

Please call me by my true names, so I can hear all my cries and my laughter at once, so I can see that my joy and pain are one.

Please call me by my true names, so I can wake up, and so the door of my heart can be left open, nthe door of compassion.

Öykü Tekten

Mountain Language

the day after the mulberry tree fell on its belly, the army bombed a truck

full of black umbrellas sent from russia against the tyranny of rain. they

said, the black umbrellas are no longer allowed in the mountains. hats

are. guns are. gods are. the trees are offensive to the sky. then

they called our language mountain, then they pronounced it dead.

we are in a dream, you said. undo the pain before you speak

against the gods with mouths full of rain. a tongue cut in half

becomes sharper, you said. date your wound.

Copyright © 2020 by Öykü Tekten. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on October 21, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

Adrienne Rich

Twenty-One Love Poems [Poem III]

Since we’re not young, weeks have to do time

for years of missing each other. Yet only this odd warp

in time tells me we’re not young.

Did I ever walk the morning streets at twenty,

my limbs streaming with a purer joy?

did I lean from any window over the city

listening for the future

as I listen here with nerves tuned for your ring?

And you, you move toward me with the same tempo.

Your eyes are everlasting, the green spark

of the blue-eyed grass of early summer,

the green-blue wild cress washed by the spring.

At twenty, yes: we thought we’d live forever.

At forty-five, I want to know even our limits.

I touch you knowing we weren’t born tomorrow,

and somehow, each of us will help the other live,

and somewhere, each of us must help the other die.

Poem III from “Twenty-One Love Poems,” from The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974-1977 by Adrienne Rich. Copyright © 1978 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

| December 26, 2020 Emilie Zoey Baker |

| I On New Year’s Eve a small river of brown snakes crossed our path What does this mean? my friends wondered I said it means we have to stay wide awake this year, pay attention. Animals are omens. II We got a kitten during lockdown and I taught him to walk on a lead we named him Panko, a tiny crumb amid a PAN-demic of CO-vid I would push a harness over his crayon sun face, then let him lick meat cream from my fingers. Now he’s tethered, clipped to a lead whenever outdoors, to save the honeyeaters, rosellas, whipbirds, cockatoos and king parrots. We nicknamed him Clippy. He comes in and out, making a cat’s cradle with the cord we have to climb over it as if he’s woven intricate laser beams in a heist movie, booby-trapped the doorway Home Aloned us. The tomato plant near the doorway is wounded from his leash, a slow cut each day like me on Twitter like every night I say it will be a new day but I wake up and think I better check if the world has ended log on to the junk feed and absorb everything I have to pay attention. III I wake up covered in dream post-it notes the urgency of action in an actionless day the news stapled into my stomach its metal claws piercing the sides I kept wishing I’d suddenly change but there have been way more aspirins than moons. My belly got big so I named it King George because mediaeval royalty wasn’t taught to body-shame. The toilet paper part of lockdown feels so long ago now the Tiger King part of lockdown the faked dolphins in Venice part of lockdown the Universal Declaration of Bunnings Rights part of lockdown the done-all-of-Brighton part of lockdown the cranberry juice and Fleetwood Mac part of lockdown the aerial shots of hospital carparks part of lockdown the marches, violence and justice part of lockdown I’m world-sick. But the snakes insisted. The prime minister waving his Sharkies scarf while we couldn’t hug our friends the prime minister offering leadership by holding a hammer (not a hose) the unwanted handshakes turning into gormless grinning elbow bumps. The air in China suddenly full of clean-crystal hope, now again heavy with particles as black as Rudy Giuliani’s skull tears. Unprecedented times. I watch it unspool. The Moses-sized divides leave me thirsty for unpresidented times. Memes blaze catastrophes duplicate. It all thumps through me like bass. IV In the beginning I saw myself like a fossil in a rock placed back into a mountain the imprinted ridges still there, clicking back like a battery I stayed quiet as the stone around me. Now I must prise myself out again. I tried to cry an ocean so the tides might bring back what was there before, wash me up to my own feet because only an ocean can dissolve a mountain. I’m not sure who I have become or what I will do. This year is vibrating with such monolithic symbolism there’s little room for poetry. Maybe making friends with a kitten is enough. V The Rockefeller Christmas owl was hunkered on a branch when they chopped her tree down and hauled it to the Rockefeller Centre. There’s a photo of the owl placed in a box looking at us with eyes like angry amber biscuits. They filled her tree with their city, added coloured lights and winding tinsel streets and called her a “stowaway”. “She wanted to see the Big Apple!” Christmas reminds us we’re monsters, shows up our Pac-Man consumerism. Blowing up ancient caves, tearing down sacred trees for three minutes of highway. Waving smirk and coal around in parliament. Decimating forests. Some cultures believe owls to be messengers for shamans to communicate with the spirit world The Rockefeller Christmas owl “got her own” children’s book. VI At yoga the teacher let it slip there’s a serpent coiled at the bottom of our spines then quickly took it back you’re not supposed to know that yet she said but that’s not the sort of thing I can unknow I googled the hell out of it. The sickeningly symbolic river of macrocosmic snakes made their way into my spine. Now I can stay awake and finally close my eyes. |

| Emilie Zoey Baker is an award-winning poet and spoken-word performer who has toured internationally including being a guest at Ubud Writers Festival, The Milosz Festival Poland and was the winner of the Berlin International Literature Festival’s poetry slam. She was a Fellow at the State Library of Victoria, poet-in-residence for Museums Victoria and coordinator for the National Australian Poetry Slam. She teaches poetry to both kids and adults and was core faculty for the spoken word program at Canada’s Banff Centre. |

Max Ritvo

Amuse-Bouche

It is rare that I

have to stop eating anything

because I have run out of it.

We, in the West, eat until we want

to eat something else,

or want to stop eating altogether.

The chef of a great kitchen

uses only small plates.

He puts a small plate in front of me,

knowing I will hunger on for it

even as the next plate is being

placed in front of me.

But each plate obliterates the last

until I no longer mourn the destroyed plate,

but only mewl for the next,

my voice flat with comfort and faith.

And the chef is God,

whose faithful want only the destruction

of His prior miracles to make way

for new ones.

From The Final Voicemails Milkweed Editions © 2018 by Max Ritvo.

William Reichard

In the Evening

The night air is filled

with the scent of apples,

and the moon is nearly full.

In the next room, Jim

is reading; a small cat sleeps

in the crook of his arm.

The night singers are loud,

proclaiming themselves

every evening until they run

out of nights and die in

the cold, or burrow down into

the mud to dream away the winter.

My office is awash in books

and photographs, and the sepia/pink

sunset stains all its light touches.

I’ve never been a good traveler,

but there are days, like this one,

when I’d pay anything to be in

another country, or standing on

the cold, grey moon, staring back

at the disaster we call our world.

We crave change, but

turn away from it.

We drown in contradictions.

Tonight, I’ll sleep

blanketed in moonlight.

In my dreams, I’ll have

nothing to say about anything

important. I’ll simply live my life,

and let the night singers live theirs,

until all of us are gone.

I won’t say a word, and let

silence speak in my stead.

Copyright © 2020 by William Reichard. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on November 19, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

Eileen Myles

Howl

a refrigerator

makes a lot

of sound

so does a bird

people are

always talking

full of love

& pain

we started

a fund

and the dogs

are needing

some money &

I don’t know how

to do

it & I’ll

learn from

one of them

Tom’s blue

shirt & glasses

are perfect.

My teeshirt

is good

my pen works

I breathe.

Copyright © 2020 by Eileen Myles. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on December 3, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

Tarfia Faizullah

Poem Full of Worry Ending with My Birth

I worry that my friends

will misunderstand my silence

as a lack of love, or interest, instead

of a tent city built for my own mind,

I worry I can no longer pretend

enough to get through another

year of pretending I know

that I understand time, though

I can see my own hands; sometimes,

I worry over how to dress in a world

where a white woman wearing

a scarf over her head is assumed

to be cold, whereas with my head

cloaked, I am an immediate symbol

of a war folks have been fighting

eons-deep before I was born, a meteor.

Copyright © 2018 by Tarfia Faizullah. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on April 10, 2018, by the Academy of American Poets.

Bei Dao

Ramallah

in Ramallah

the ancients play chess in the starry sky

the endgame flickers

a bird locked in a clock

jumps out to tell the time

in Ramallah

the sun climbs over the wall like an old man

and goes through the market

throwing mirror light on

a rusted copper plate

in Ramallah

gods drink water from earthen jars

a bow asks a string for directions

a boy sets out to inherit the ocean

from the edge of the sky

in Ramallah

seeds sown along the high noon

death blossoms outside my window

resisting, the tree takes on a hurricane’s

violent original shape

“Ramallah” by Bei Dao, from World Beat: International Poetry Now, copyright 2006 by Zhao Zhenkai, Translation © Eliot Weinberger and Iona Man-Cheong. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Ocean Vuong

Kissing in Vietnamese

My grandmother kisses

as if bombs are bursting in the backyard,

where mint and jasmine lace their perfumes

through the kitchen window,

as if somewhere, a body is falling apart

and flames are making their way back

through the intricacies of a young boy’s thigh,

as if to walk out the door, your torso

would dance from exit wounds.

When my grandmother kisses, there would be

no flashy smooching, no western music

of pursed lips, she kisses as if to breathe

you inside her, nose pressed to cheek

so that your scent is relearned

and your sweat pearls into drops of gold

inside her lungs, as if while she holds you

death also, is clutching your wrist.

My grandmother kisses as if history

never ended, as if somewhere

a body is still

falling apart.

Copyright © 2014 by Ocean Vuong. Reprinted from Split This Rock’s The Quarry: A Social Justice Poetry Database.

Brenda Shaughnessy

One Love Story, Eight Takes

Where you are tender, you speak your plural.

Roland Barthes

1

One version of the story is I wish you back—

that I used each evening evening out

what all day spent wrinkling.

I bought a dress that was so extravagantly feminine

you could see my ovaries through it.

This is how I thought I would seduce you.

This is how frantic I hollowed out.

2

Another way of telling it

is to hire some kind of gnarled

and symbolic troll to make

a tape recording.

Of plastic beads coming unglued

from a child’s jewelry box.

This might be an important sound,

like serotonin or mighty mitochondria,

so your body hears about

how you stole the ring made

from a glittery opiate

and the locket that held candy.

3

It’s only fair that I present yet another side,

as insidious as it is,

because two sides hold up nothing but each other.

A tentacled skepticism,

a suspended contempt,

such fancies and toxins form a third wall.

A mean way to end

and I never dreamed we meant it.

4

Another way of putting it is like

slathering jam on a scrape.

Do sweets soothe pain or simply make it stick?

Which is the worst! So much technology

and no fix for sticky if you can’t taste it.

I mean there’s no relief unless.

So I’m coming, all this excitement,

to your house. To a place where there’s no room for play.

It is possible you’ll lock me out and I’ll finally

focus on making mudcakes look solid in the rain.

5

In some cultures the story told is slightly different—

in that it is set in an aquarium and the audience participates

as various fish. The twist comes when it is revealed

that the most personally attractive fish have eyes

only on one side and repel each other like magnets.

The starfish is the size of an eraser and does as much damage.

Starfish, the eponymous and still unlikely hero, has

those five pink moving suckerpads

that allow endless permutations so no solid memory,

no recent history, nothing better, left unsaid.

6

The story exists even when there are no witnesses,

kissers, tellers. Because secrets secrete,

and these versions tend to be slapstick, as if in a candy

factory the chocolate belted down the conveyor too fast

or everyone turned sideways at the same time by accident.

This little tale tries so hard to be humorous,

wants so badly to win affection and to lodge.

Because nothing is truly forgotten and loved.

7

Three million Richards can’t be wrong.

So when they levy a critique of an undertaking which,

in their view, overtakes, I take it seriously.

They think one may start a tale off whingy

and wretched in a regular voice.

But when one strikes out whimsically,

as if meta-is-better, as if it isn’t you,

as if this story is happening to nobody

it is only who you are fooling that’s nobody.

The Richards believe you cannot

privately jettison into the sky, just for fun.

You must stack stories from the foundation up.

From the sad heart and the feet tired of supporting it.

Language is architecture, after all, not an air capsule,

not a hang glide. This is real life.

So don’t invite anyone to a house that hasn’t been built.

Because no one unbuilds meticulously

and meticulosity is what allows hearing.

Three million Richards make one point.

I hear it in order to make others. Mistake.

8

As it turns out, there is a wrong way to tell this story.

I was wrong to tell you how muti-true everything is,

when it would be truer to say nothing.

I’ve invented so much and prevented more.

But, I’d like to talk with you about other things,

in absolute quiet. In extreme context.

To see you again, isn’t love revision?

It could have gone so many ways.

This just one of the ways it went.

Tell me another.

Brenda Shaughnessy, “One Love Story, Eight Takes” from Human Dark with Sugar, Copper Canyon Press. Copyright © 2008 by Brenda Shaughnessy. http://www.coppercanyonpress.org

Donna Stonecipher

The Ruins of Nostalgia 59

We felt nostalgic for libraries, even though we were sitting in a library. We looked around the library lined with books and thought of other libraries we had sat in lined with books and then of all the libraries we would never sit in lined with books, some of which contained scenes set in libraries. * We felt nostalgic for post offices, even though we were standing in a post office. We studied the rows of stamps under glass and thought about how their tiny castles, poets, cars, and flowers would soon be sent off to all cardinal points. We rarely got paper letters anymore, so our visits to the post office were formal, pro forma. * We felt nostalgic for city parks, even though we were walking through a city park, in a city full of city parks in a country full of cities full of city parks, with their green benches, bedraggled bushes, and shabby pansies, cut into the city. (Were the city parks bits of nature showing through cutouts in the concrete, or was the concrete showing through cutouts in nature?) * We sat in a café drinking too much coffee and checking our feeds, wondering why we were more anxious about the future than anxiously awaiting it. Was the future showing through cutouts in the present, or were bits of the present showing through cutouts in a future we already found ourselves in, arrived in our café chairs like fizzled jetpacks? The café was in a former apothecary lined with dark wood shelves and glowing white porcelain jars labeled in gilded Latin, which for many years had sat empty. Had a person with an illness coming to fetch her weekly dose of meds from one of the jars once said to the city surrounding the shop, which was no longer this city, Stay, thou art so fair? Weren’t these the words that had sealed the bargainer’s doom? Sitting in our presumptive futures, must we let everything run through our hands—which were engineered to grab—into the past? In the library, in the post office, in the city park, in the café, in the apothecary… o give us the medicine, even if it is a pharmakon—which, as the pharmacist knows, either poisons or heals—just like nostalgia. Just like the ruins of nostalgia.

Copyright © 2020 by Donna Stonecipher. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on December 8, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

Suji Kwock Kim

Search Engine: Notes from the North Korean-Chinese-Russian Border

By which a strip of land became a hole in time

—Durs Grünbein

Grandfather I cannot find,

flesh of my flesh, bone of my bone,

what country do you belong to:

where is your body buried,

where did your soul go

when the road led nowhere?

Grandfather I’ll never know,

the moment father last saw you

rips open a wormhole

that has no end: the hours

became years, the years

forever: and on the other side

lies a memory of a memory

or a dream of a dream of a dream

of another life, where what happened

never happened, what cannot come true

comes true: and neither erases

the other, or the other others,

world after world, to infinity—

If only I could cross the border

and find you there,

find you anywhere,

as if you could tell me who he is, or was,

or might have become:

no bloodshot eyes, or broken

bottles, or praying with cracked lips

because the past is past and was is not is—

Grandfather, stranger,

give me back my father—

or not back, not back, give me the father

I might have had:

there, in the country that no longer exists,

on the other side of the war—

Copyright © 2019 by Suji Kwock Kim. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on December 6, 2019, by the Academy of American Poets.

Adrienne Rich

Diving into the Wreck

First having read the book of myths,

and loaded the camera,

and checked the edge of the knife-blade,

I put on

the body-armor of black rubber

the absurd flippers

the grave and awkward mask.

I am having to do this

not like Cousteau with his

assiduous team

aboard the sun-flooded schooner

but here alone.

There is a ladder.

The ladder is always there

hanging innocently

close to the side of the schooner.

We know what it is for,

we who have used it.

Otherwise

it is a piece of maritime floss

some sundry equipment.

I go down.

Rung after rung and still

the oxygen immerses me

the blue light

the clear atoms

of our human air.

I go down.

My flippers cripple me,

I crawl like an insect down the ladder

and there is no one

to tell me when the ocean

will begin.

First the air is blue and then

it is bluer and then green and then

black I am blacking out and yet

my mask is powerful

it pumps my blood with power

the sea is another story

the sea is not a question of power

I have to learn alone

to turn my body without force

in the deep element.

And now: it is easy to forget

what I came for

among so many who have always

lived here

swaying their crenellated fans

between the reefs

and besides

you breathe differently down here.

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

I stroke the beam of my lamp

slowly along the flank

of something more permanent

than fish or weed

the thing I came for:

the wreck and not the story of the wreck

the thing itself and not the myth

the drowned face always staring

toward the sun

the evidence of damage

worn by salt and sway into this threadbare beauty

the ribs of the disaster

curving their assertion

among the tentative haunters.

This is the place.

And I am here, the mermaid whose dark hair

streams black, the merman in his armored body.

We circle silently

about the wreck

we dive into the hold.

I am she: I am he

whose drowned face sleeps with open eyes

whose breasts still bear the stress

whose silver, copper, vermeil cargo lies

obscurely inside barrels

half-wedged and left to rot

we are the half-destroyed instruments

that once held to a course

the water-eaten log

the fouled compass

We are, I am, you are

by cowardice or courage

the one who find our way

back to this scene

carrying a knife, a camera

a book of myths

in which

our names do not appear.

From Diving into the Wreck: Poems 1971-1972 by Adrienne Rich. Copyright © 1973 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Copyright 1973 by Adrienne Rich.

Hsieh Ling-yun

Visiting Pai-an Pavilion

Beside this dike, I shake off the world's dust, enjoying walks alone near my brushwood house. A small stream gurgles down a rocky gorge. Mountains rise beyond the trees, kingfisher blue, almost beyond description, but reminding me of the fisherman's simple life. From a grassy bank, I listen as springtime fills my heart. Finches call and answer in the oaks. Deer cry out, then return to munching weeds. I remember men who knew a hundred sorrows, and the gratitude they felt for gifts. Joy and sorrow pass, each by each, failure at one moment, happy success the next. But not for me. I have chosen freedom from the world's cares. I chose simplicity.

From Crossing the Yellow River: Three Hundred Poems from the Chinese, translated and edited by Sam Hamill. Translation copyright © 2000 by Sam Hamill. Reprinted by permission of translator and publisher. All rights reserved.

Jane Hirshfield

The Bowl

If meat is put into the bowl, meat is eaten.

If rice is put into the bowl, it may be cooked.

If a shoe is put into the bowl,

the leather is chewed and chewed over,

a sentence that cannot be taken in or forgotten.

A day, if a day could feel, must feel like a bowl.

Wars, loves, trucks, betrayals, kindness,

it eats them.

Then the next day comes, spotless and hungry.

The bowl cannot be thrown away.

It cannot be broken.

It is calm, uneclipsable, rindless,

and, big though it seems, fits exactly in two human hands.

Hands with ten fingers,

fifty-four bones,

capacities strange to us almost past measure.

Scented—as the curve of the bowl is—

with cardamom, star anise, long pepper, cinnamon, hyssop.

—2014

from Ledger (Knopf, 2020); first appeared in Brick.

Franny Choi

Hangul Abecedarian

Gathering sounds from each provincial

Nook and hilly village, the scholars

Discerned differences between

Long and short vowels, which phonemes,

Mumbled or dipthonged, would become

Brethren, linguistically speaking.

Speaking of taxonomy,

I’ve been busy categorizing what’s

Joseon, what’s American about each

Choice of diction or hill I might die on.

Killing my accent was only ever half the

Task, is what I mean. Q: When grief

Pushes its wet moons from me, is the sound

Historically accurate? or just a bit of feedback?

Copyright © 2020 by Franny Choi. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on May 20, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

Jane Mead

I Have Been Living

I have been living closer to the ocean than I thought-- in a rocky cove thick with seaweed. It pulls me down when I go wading. Sometimes, to get back to land takes everything that I have in me. Sometimes, to get back to land is the worst thing a person can do. Meanwhile, we are dreaming: The body is innocent. She has never hurt me. What we love flutters in us.

From House of Poured Out Waters © 2000 by Jane Mead.

Marilyn Chin

Sage #3

(This poem’s about looking for the sage and not finding her)

Some say she moved in with her ex-girlfriend in Taiwan

Some say she went to Florida to wrestle alligators

Some say she went to Peach Blossom Spring

To drink tea with Tao Qian

Miho says she’s living in Calexico with three cats

And a gerbil named Max

Some say she’s just a shadow of the Great Society

A parody

Of what might-have-been

Rhea saw her stark raving mad

Between 23rd and the Avenue of the Americas

Wrapped in a flag!

I swear I saw her floating in a motel pool

Topless, on a plastic manatee, palms up

What in hell was she thinking?

What is poetry? What are stars?

Whence comes the end of suffering?

Copyright © 2020 by Marilyn Chin. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on May 13, 2020 by the Academy of American Poets.

Conrad Aiken

from “1915: The Trenches”

II.

All night long we lie

Stupidly watching the smoke puff over the sky,

Stupidly watching the interminable stars

Come out again, peaceful and cold and high,

Swim into the smoke again, or melt in a flare of red…

All night long, all night long,

Hearing the terrible battle of guns,

We smoke our pipes, we think we shall soon be dead,

We sleep for a second, and wake again,

We dream we are filling pans and baking bread,

Or hoeing the witch-grass out of the wheat,

We dream we are turning lathes,

Or open our shops, in the early morning,

And look for a moment along the quiet street…

And we do not laugh, though it is strange

In a harrowing second of time

To traverse so many worlds, so many ages,

And come to this chaos again,

This vast symphonic dance of death,

This incoherent dust.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on December 23, 2018, by the Academy of American Poets.

“1915: The Trenches” was published in Nocturne of a Remembered Spring and Other Poems (The Four Seas Company, 1917).

Jane Hirshfield

I wanted to be surprised.

To such a request, the world is obliging.

In just the past week, a rotund porcupine,

who seemed equally startled by me.

The man who swallowed a tiny microphone

to record the sounds of his body,

not considering beforehand how he might remove it.

A cabbage and mustard sandwich on marbled bread.

How easily the large spiders were caught with a clear plastic cup

surprised even them.

I don’t know why I was surprised every time love started or ended.

Or why each time a new fossil, Earth-like planet, or war.

Or that no one kept being there when the doorknob had clearly.

What should not have been so surprising:

my error after error, recognized when appearing on the faces of others.

What did not surprise enough:

my daily expectation that anything would continue,

and then that so much did continue, when so much did not.

Small rivulets still flowing downhill when it wasn’t raining.

A sister’s birthday.

Also, the stubborn, courteous persistence.

That even today please means please,

good morning is still understood as good morning,

and that when I wake up,

the window’s distant mountain remains a mountain,

the borrowed city around me is still a city, and standing.

Its alleys and markets, offices of dentists,

drug store, liquor store, Chevron.

Its library that charges—a happy surprise—no fine for overdue books:

Borges, Baldwin, Szymborska, Morrison, Cavafy.

—2018

from Ledger (Knopf, 2020); first appeared in The New Yorker.

Jane Hirshfield

On the Fifth Day

On the fifth day

the scientists who studied the rivers

were forbidden to speak

or to study the rivers.

The scientists who studied the air

were told not to speak of the air,

and the ones who worked for the farmers

were silenced,

and the ones who worked for the bees.

Someone, from deep in the Badlands,

began posting facts.

The facts were told not to speak

and were taken away.

The facts, surprised to be taken, were silent.

Now it was only the rivers

that spoke of the rivers,

and only the wind that spoke of its bees,

while the unpausing factual buds of the fruit trees

continued to move toward their fruit.

The silence spoke loudly of silence,

and the rivers kept speaking

of rivers, of boulders and air.

Bound to gravity, earless and tongueless,

the untested rivers kept speaking.

Bus drivers, shelf stockers,

code writers, machinists, accountants,

lab techs, cellists kept speaking.

They spoke, the fifth day,

of silence.

—2017

from Ledger (Knopf, 2020); first appeared in The Washington Post.

Charles Simic

Pigeons at Dawn

Extraordinary efforts are being made To hide things from us, my friend. Some stay up into the wee hours To search their souls. Others undress each other in darkened rooms. The creaky old elevator Took us down to the icy cellar first To show us a mop and a bucket Before it deigned to ascend again With a sigh of exasperation. Under the vast, early-dawn sky The city lay silent before us. Everything on hold: Rooftops and water towers, Clouds and wisps of white smoke. We must be patient, we told ourselves, See if the pigeons will coo now For the one who comes to her window To feed them angel cake, All but invisible, but for her slender arm. Copyright © 2005 by Charles Simic. From My Noiseless Entourage, of Harcourt Inc.

C Dale Young

Melancholia

The whirring internal machine, its gears

grinding not to a halt but to a pace that emits

a low hum, a steady and almost imperceptible

hum: the Greeks would not have seen it this way.

Simply put, it was a result of black bile,

the small fruit of the gall bladder perched

under the liver somehow over-ripened

and then becoming fetid. So the ancients

would have us believe. But the overly-emotional

and contrarian Romans saw it as a kind of mourning

for one’s self. I trust the ancients but I have never

given any of this credence because I cannot understand

how one does this, mourn one’s self.

Down by the shoreline—the Pacific

wrestling with far more important

philosophical issues—I recall the English notion

of it being a wistfulness, something John Donne

wore successfully as a fashion statement.

But how does one wear wistfulness well

unless one is a true believer?

The humors within me are unbalanced,

and I doubt they were ever really in balance

to begin with, ever in that rare but beautiful

thing the scientists call equilibrium.

My gall bladder squeezes and wrenches,

or so I imagine. I am wistful and morose

and I am certain black bile is streaming

through my body as I walk beside this seashore.

The small birds scrambling away from the advancing

surf; the sun climbing overhead shortening shadows;

the sound of the waves hushing the cries of gulls:

I have no idea where any of this ends up.

To be balanced, to be without either

peaks or troughs: do tell me what that is like…

This contemplating, this mulling over, often leads

to a moment a few weeks from now,

the one in which everything suddenly shines

with clarity, where my fingers race to put down

the words, my fingers so quick on the keyboard

it will seem like a god-damned miracle.

Copyright © 2020 by C. Dale Young. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on October 13, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

Jennifer Tseng

Dear Nainai,

Every day you sink into her To make room for me. When I die, I sink into you, When Xing dies, she sinks Into me, her child dies & Sinks into Xing & the Earth, Who is always ravenous, Swallows us. I don’t know where you’re buried. I don’t know your sons’ names, Only their numbers & fates: #2 was murdered, #3 went to jail, #4 hung himself, #5, who did the cooking & cleaning, is alive. #1, my father, died of pancreatic cancer. Of bacon & lunch meat & Napoleons. Your husband died young, of Double Happiness, unfiltered. You died of Time, Of motherhood, Of being the boss, Of working in a sock factory, Of an everyday ailment For which there is no cure. I am alone, like a number. #1 writes me a letter: My dearest Jenny, Do you know Rigoberta Menchú, this name? There were also silences about Chinese girls, Oriental women. In field of literature, you must be strong enough to bear all these. An ivory tower writer can never be successful. You are almost living like a hermit. Are you coming home soon? He doesn’t mention you. Perfect defect. Hidden flaw in the cloth, Yellow bead in the family regalia. Bidden to be understory, Silences, pored & poured over. You are almost living. You say hello to me quietly. What is success? Meat? Pastries? Cigarettes? The cessation of Communion with self? I want to be eaten By an ivory tower, Devoured by the power Of my own solitude. We’re alone together. I read the letter every day before death. Where are you buried, Nainai? I’m coming home soon.

Copyright © 2019 by Jennifer Tseng. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on January 25, 2019, by the Academy of American Poets.

Nicole Sealey

The First Person Who Will Live to Be One Hundred and Fifty Years Old Has Already Been Born

[For Petra]

Scientists say the average human

life gets three months longer every year.

By this math, death will be optional. Like a tie

or dessert or suffering. My mother asks

whether I’d want to live forever.

“I’d get bored,” I tell her. “But,” she says,

“there’s so much to do,” meaning

she believes there’s much she hasn’t done.

Thirty years ago she was the age I am now

but, unlike me, too industrious to think about

birds disappeared by rain. If only we had more

time or enough money to be kept on ice

until such a time science could bring us back.

Of late my mother has begun to think life

short-lived. I’m too young to convince her

otherwise. The one and only occasion

I was in the same room as the Mona Lisa,

it was encased in glass behind what I imagine

were velvet ropes. There’s far less between

ourselves and oblivion—skin that often defeats

its very purpose. Or maybe its purpose

isn’t protection at all, but rather to provide

a place, similar to a doctor’s waiting room,

in which to sit until our names are called.

Hold your questions until the end.

Mother, measure my wide-open arms—

we still have this much time to kill.

Copyright © 2017 by Nicole Sealey. Originally published in The Village Voice.