My father died a year ago this week. He died on my parents’ bed, at his home, with his head propped against my solar plexus, supported by my crossed legs, as I stroked his arms. At the bottom of the bed our family was arrayed: my sister, my mother, my brother-in-law – my brother-in-law attendant throughout.

My father labored some hours to die, spewing black bile in repeated bouts.

“Tastes bad,” he murmured.

“Amazing how hard the body holds on to life,” my brother-in-law said, quietly.

After my father’s body gave up, I checked under his jaw for a pulse, checked my finger under his nostril for breath. I scooped the black bile out of his mouth and throat with a damp washcloth, cleaned his teeth and gums, before the palliative nurse, who we’d met just once, the previous day, arrived belatedly.

“I forgive you everything you’ve ever done wrong, for this,” my sister told me.

That’s how it was.

I wrote my father’s eulogy two days before he died.

After I delivered my eulogy at his commemorative celebration, a packed event at a local community hall, I realized I’d left out something important.

I talked about my father’s sense of humour, his way with words, his way with people. I talked in code about what an argumentative cuss he could be, a dinner table bigot. I talked about his vast curiosity. I talked about how much we loved him, and how much he loved our mother.

I left out something so obvious it blinds me: I left out my father the carer.

When my father was diagnosed with advanced, untreatable pancreatic cancer 11 weeks before his death, his immediate response was ‘So now would be a good time to buy a new car?”

He bought a new car the next day, for my mother. The car she’d been using, the one with seats that were too low, he instructed should be for my use.

When his GP responded he wished all his patients were like my dad, Dad laughed “What, dying?”

Expecting to live six weeks or less, my father spent the next weeks immersed in ensuring financial and administrative matters were in order, that the family would be cared for.

He could barely eat, just crackers, tea and packet soup. He ate a stale Cherry Ripe. Then he hunched over a garden border bed and threw up, painful retching that raised his shoulders, thin strains of pink-strewn chocolate residue. I stood close by his side with my hands soothing his back.

When he was finished, when he straightened, he whispered to me, “That’s what I did for my Mum.”

He held bowls to his mother’s lips as she threw up, dying of cancer.

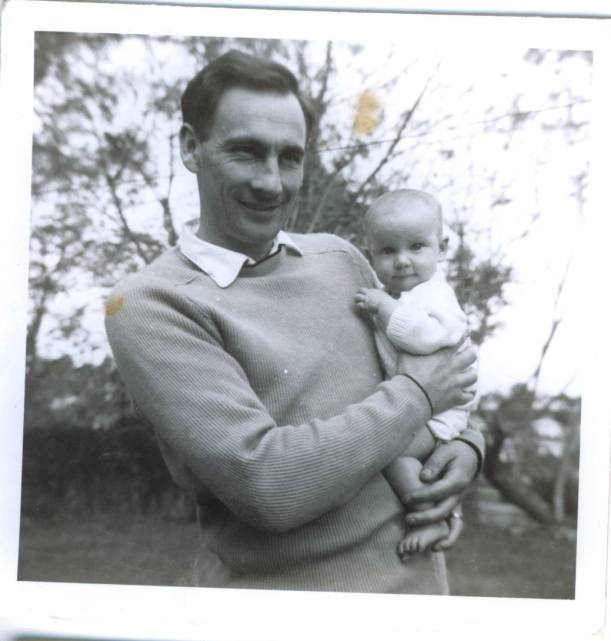

My father lived twice as long as expected after diagnosis. His mother held on for four years. My father was at university in Melbourne when his mother was first diagnosed. He thrived in Melbourne. He had close friends and exciting prospects. He was doing some tutoring, some teaching at his old boarding college. He had offers of work abroad for foreign governments, offers of postgrad study.

Instead, he returned to the country town where his parents lived, where they lived somewhat unhappily together, on the border of South Australia and Victoria. His parents lived with his sister and his mother’s sister, who kept house and nursed his mother.

He helped nursed his mother and he worked in his father’s shop.

Every weekend, as soon as he knocked off work at the shop, he leapt in his 1950s jalopy and drove as fast as he could – which was fast – to Melbourne. A bit over five hours. There he went on pub-crawls with his mates and bet at the racetracks. Then Sunday night he drove the 430km back to Mount Gambier.

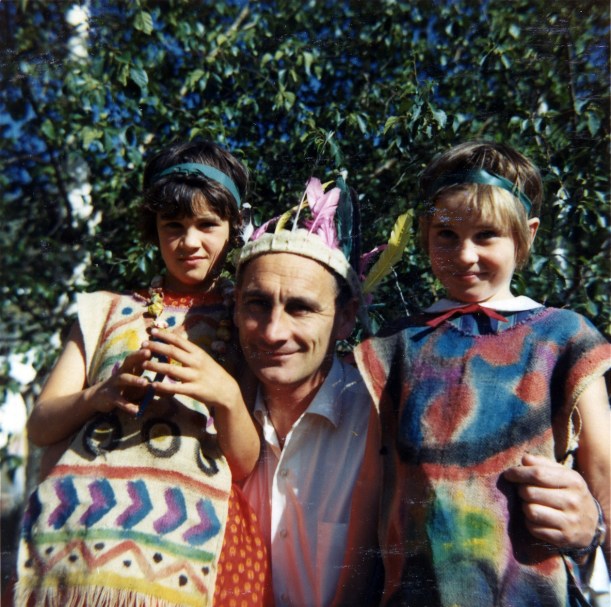

After his mother died, after he’d married my mother, moved to Brisbane, had two infants, my mother would complain about him staying out late after work playing cards with his mates. I don’t know how frequent this was. I do know that before I was 18 months old we’d moved to Mount Gambier, stayed at his parents’ house, then moved to Adelaide, where we lived the next 11 years. Every couple of weeks my father would drive to Mount Gambier – about 5 hours, about 430km – to spend a weekend with his father and his disabled older sister, taking care of what needed taking care of.

Which was a lot. My grandfather had glaucoma and was blind. My father’s much-older sister had crippled legs and cognitive impairment, a legacy of polio in about 1920 compounded by some illness undetermined: meningitis, encephalitis, Murray River Fever. Something fearful.

Their house was huge, built in 1910. Maintenance was massive.

When it was obvious my grandfather and my aunt could no longer manage there, obvious even to my grandfather and my aunt, my father bought them a smaller house a street away. He arranged the sale of the big house. He fought court battles when the sale fell through and he stood accused by the erstwhile buyer of misrepresentation (the buyer claimed Dad had filled the bathtub with books, so the buyer couldn’t see the poor condition of the tub).

My parents, my sister and I were now living in Melbourne. When my grandfather had cancer and was dying, my father drove up and down that highway constantly. He was due the evening my grandfather died. Freak thunderstorms lit up lurid skies. My father decided it wasn’t safe to drive, better the next day. My grandfather lay in his bed in his new home and kept asking, “When will Angus be here?”

In his last days my father confided he was certain his father’s longtime doctor had given him a morphine overdose that last night, at my grandfather’s request, the both of them expecting my father to arrive for the death.

My father felt he’d failed his dad.

After his father’s death, my father bought a small house a short walk from the home where he’d retired with my mother and moved his sister in there. He supported her living in that house until she needed round the clock care. No facility was willing to take her – “special needs” – so he donated generously till a local aged care home relented.

When she died, he cried. He released yellow balloons at her funeral. He said, “That’s over. The Great Obligation.”

My father financially supported his mother’s sister, who’d nursed his mother through her dying years and remained to keep house after my father married and moved to Brisbane. He ensured his aunt could continue to live independently, in her own flat, through to her death.

I believe he provided some financial support for others in his father’s 11 siblings’ families.

When my mother’s mother died and her father went the full King Lear, my father provided what care he could. When others in our family periodically went mad over the next decades, he supported us.

When I struggled financially, which is to say, my late 20s, early 30s, and pretty much always past age 40, my father played pater familias and ensured I was not homeless. I resented that mightily.

When I had bouts of depression after his death, when I thought life tasted sour, my sister said, “You can’t check out. Not after all the effort he put into keeping you alive.”

Fair point.

Here is the eulogy I didn’t deliver, the eulogy to my father, the carer.

Thank you for my life.