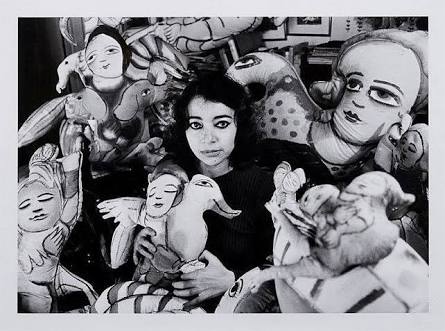

Call me Jacks – Jacqueline Pearce in conversation [with Nicholas Briggs] Audio CD

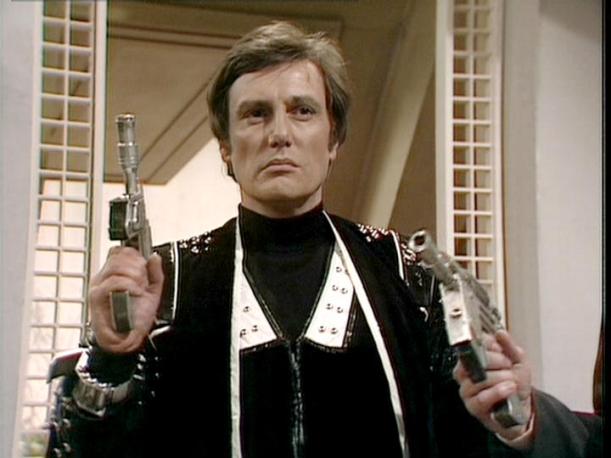

You’re him, aren’t you? An autobiography by Paul Darrow

From 1978 till 1981 the British sci-fi series Blake’s 7 was broadcast on TV across four seasons, 52 episodes in all. Blake’s 7 was originated by Terry Nation, who also created the Daleks of Doctor Who fame. He intended Blake’s 7 to be a darker alternative to Doctor Who: Doctor Who for adults. Or a darker Star Wars. It ended badly. I mean that. As a 20 year old fan in 1981, I was so distressed by Blake’s 7’s final scenes that I wrote to the newspapers: Shocked of Kings Cross, Sydney (a neighbourhood where most of us were mostly unshockable).

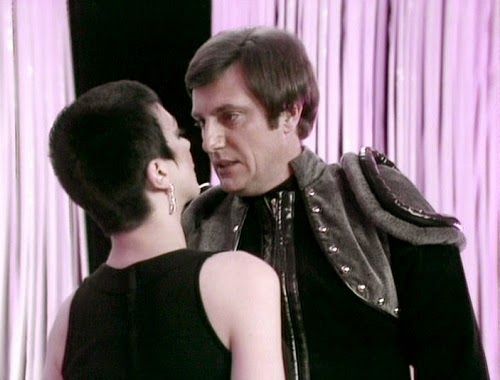

There were two mainstay characters who did not appear in Episode 1, Series 1, and one of these characters was missing – and greatly missed – in that final episode. The other claims the final shot. These characters are the evil galactic Supreme Commander Servalan, played by Jacqueline Pearce, and Avon, first introduced as a cold, self-interested, sociopathic hacker, played by Paul Darrow.

The absence of Servalan and Avon might explain why, when I watched a repeat of Episode 1, Series 1 when Blake’s 7 was rescreened in the ‘90s, I could not make out why I’d loved this show so much. Avon and Servalan. They were the drawcards. Tarrant was cute and Cally quite compelling, Vila was amusing and the first Travis had a kind of S&M appeal, but really, for me Blake’s 7 was Avon and Servalan. This I understand was true for many of the series’ 10 million or so (at its peak) viewers.

Servalan, especially, was a kind of perverted role model for me. After a miserable love affair, I cut my hair to a short fuzz, to look like hers. Men wanted to touch the possum fur fuzz on my head. I let them. But I knew I was an alter ego – a lost clone – of the Supreme Commander and that if I chose, those men would be laser blast fragments.

Having recently re-encountered Blake’s 7, I was curious to learn what happened to the actors in their subsequent lives. I found there is a pop cult industry around the series, a business called B7 and a business called Big Finish, with audio adventures voiced by original cast members and Comic Con appearances. There are autobiographical materials, such as Call Me Jacks – Jacqueline Pearce in conversation (audio CD) and Paul Darrow’s memoir You’re him, aren’t you? – An autobiography.

What did I learn?

I learned that it’s painful to be an actor, that the odds of achieving any kind of success are stacked against acting aspirants, that success once achieved is seldom enough, and seldom sustained, and that the pain of being a has-been and the pain of being a never-was and the pain of finding hollow “success” can be hard to live with.

I learned that Darrow and Pearce are both deeply ambivalent about Blake’s 7, that the 35 years since have seen both struggle with depression and despair, and struggle in other ways. Pearce talks openly, recklessly, about it. Darrow circles around pain and disappointment over and over, looping through themes of ambition and failure, and feelings of anger and envy, till the cumulative effect is of an old actor, deep in his cups, holding forth in a way he hopes is avuncular but in fact comes across as bitter. Not that I’m saying Paul Darrow drinks. I’m talking about how I read his memoir.

There are positives. Jacqueline Pearce is painfully open, recounting a tale of talent blighted by mental illness, but her story testifies to resilience and the value of friendships, including a supportive friendship with the late great actor John Hurt. It’s easy to empathise with Pearce’s observations and experiences, and easy to admire her fortitude. Plus, her voice is beautiful, even if her frequent throaty laugh becomes unsettling.

Paul Darrow is an intelligent man and his account of his life attests resilience, too, and enterprise. He writes in short pieces, not necessarily linear chronology, and I wish there’d been a sympathetic editor to hand to help him focus on the interesting questions he raises, and to minimise some of the more indulgent sections, such as his synopses of each episode of every Blake’s 7 series, which could be summarised as “The narratives were crap, the production values trash; if you care about Blake’s 7, the more fool you.”

I don’t think he meant to imply Blake’s 7’s production team, or its viewers, are idiots, but he does imply that, at length. Then he contradicts himself and praises the writers, the directors, the stunt crew, thanks the actors for their friendship and thanks Terry Nation for transforming his life. Like I said, conflicted.

Paul Darrow is an intelligent man. He does raise good questions. Given the plots are ludicrous, the stunts unconvincing, special effects rudimentary and the production values shout low budget, what can account for Blake’s 7’s popularity? This was a show shot on video, not film, shot largely within semi-bare stationary sets (Scene: The interior of a space craft), with quarries and occasional sand drifts for location shoots, and characters who wield what look like hair-dryers standing in for laser guns.

And this: why did audiences relate so strongly to the overt sociopaths, to Avon and Servalan? Why did the sparks of an Avon/Servalan pairing cause salivations? Why, cosmos above, would young women like me imagine Servalan a role model and fantasise about Avon?

Paul Darrow is an intelligent man and in his autobiography he acknowledges these questions. Then, after a half-hearted stab in response (Avon as “a bit of rough”?), he gloomily gives up, as if it’s all too much. Which it would seem it was.

It must be hard, for Paul Darrow, to start out sharing a house with fellow RADA students John Hurt and Ian McShane, and at the height of one’s fame to be touted as a future James Bond (Timothy Dalton got the Bond gig), then to be relegated to pantomime, touring rep (again), and the continuing audio adventures of a character you played several decades back. A character who logic suggests died.

Darrow writes interestingly about typecasting, and he writes about an actor’s need for an audience, for affirmation. He is savagely funny about how he’ll be remembered. As ever, he’s torn, not sure whether anyone will care at all, or whether there’ll be mangled memories and pop culture fan-hysteric tears, or whether some people might consider his career had value. I’m here to reassure him. Paul, you are loved. How could a reader not love an actor who quotes the review that said “Paul Darrow plays Macbeth like Freddie Mercury giving a farewell concert”, and the review that read “Paul Darrow is an actor worth watching, but not in this play”?

It must be hard, for Jacqueline Pearce, to start out as the RADA ‘girl most likely’, directed by Trevor Nunn, hanging out with John Hurt, Anthony Hopkins and Ian McShane (no mention of Paul Darrow), then be ‘demoted’ in the final series of Blake’s 7, omitted altogether from the final episode, then spend most of the next decades with little or no acting work, instead dependent on Housing Benefits and the kindness of friends, with stints as an artists’ life-drawing nude model in Cornwall, and volunteering in a monkey sanctuary in Africa. Plus stints in psychiatric care. And two bouts with cancer.

Live well, Jacqueline.

My own best answer for why Blake’s 7 was loved is this:

In the late ‘70s, the Western world began to understand its supremacy could not last. Throughout the ‘70s there were petrol politics, revolutions, the Irish Troubles, labour unrest, increasing disparity between North and South, and rich and poor. During Blake’s 7’s run, the USA voted out Jimmy Carter and voted in Ronald Reagan. Margaret Thatcher was elected prime minister of Britain.

We weren’t too sure about our heroes – was Thatcher a Servalan? – and we weren’t sure who were the villains (the IRA? Revolutionaries in Iran?).

Paul Darrow points out it isn’t clear whether the crew of the space ship Liberator, the crew who were “Blake’s seven”, were in fact heroes or simply terrorists. He asks, if Blake was trying to lead a popular revolution, why was nobody else rising up? Could it be, possibly, that the Evil Empire was not perceived by its citizens as evil? Could it be that Blake, and his crew, with their talents for destruction, remained criminals even on the Liberator, as they had started out criminals?

In times of change and extreme moral ambivalence the foremost task, possibly, becomes survival. Avon and Blake and the Blake’s 7 crew hurtled through a hostile universe, hunted by omnipresent authorities, unsure of their mission, not knowing who to trust. So you trust the strong man. You trust the sociopath, Avon, because Avon has his eyes on the prize: survival. Or you follow the Supreme Commander, Servalan, because Servalan is also a survivor, and her will to power is second to none.

Pearce and Darrow were good at playing survivors.

Don’t be fooled by that soft velvet fuzz. Servalan will kill rather than be killed, and Avon will, always, be the last man standing.