A murder will occur tonight in a crumbling stately heap named Blackheath, at 11pm. You know who the victim is.* Your mission – and you have no choice but to accept – is to identify the killer. You have eight days to do this: the same day will repeat, Groundhog Day-like, eight times; each day you will inhabit the body (and assimilate some mental traits) of a different witness. Make good use of each window to investigate.

Each day you will co-exist alongside – interact with – your other iterations. You may discover who they are as the days repeat. You may offer to collaborate. They may – or may not – do so.

You are in competition with two other souls tasked with the same mission. The first correct answer wins. The winner will be returned to his/her initial identity, have his/her memory restored, and will be permitted to leave this place. The two laggards will not.

Oh. Watch out for the sociopathic sadist footman. Footman, as in attendant on a hunting shoot. Btw: almost every guest invited to Blackheath’s masque ball and hunt has brought a footman. Which is the one?

And who is Anna?

This is the premise for The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle, which its author describes as a “time-travel, body-hopping murder-mystery novel”. The cover blurbs refer to it as “unique” and “original”, as if this territory isn’t worked repeatedly by David Mitchell (The Body Clocks, Slade House), and as if the plot construction doesn’t owe a debt to games design. But I’ll grant it’s “darkly comic, mind-blowingly twisty”, “energising and clever”, and given his vision of grafting time travel, body-hopping onto an Agatha Christie-style English Country House Weekend murder mystery, I’ll grant Stuart Turton the title “the Mad Hatter of crime”.

Turton himself refers to the genesis of his novel as “Lynchian”, referring to filmmaker David Lynch.

Allowing the narrator’s consciousness to live in the present tense through the vehicles of eight other individuals permits multiple perspectives on solving the murder. The narrator, who we learn has voluntarily submitted himself to this bizarre “puzzle box house”, Blackheath, is, we are given to understand, one Aiden Bishop.

Bishop is a moral character, a character who believes in justice and subscribes to judgement. His musings invite the reader to engage in multiple moral perspectives. Which loyalties carry most weight? Is redemption possible? Can an evil person work good? Can seemingly inevitable futures be averted?

A masked man in a black-feathered coat, known as the Plague Doctor, tells him

“Nothing that’s happening here is inevitable, much as it may appear otherwise. Events keep happening the same way day after day, because your fellow guests keep making the same decisions day after day. […] They cannot see another way, so they never change. You are different, Mr Bishop. […] You make different decisions, and yet repeat the same mistakes at crucial junctures. It’s as if some part of you is perpetually pulled towards the pit.”

The Plague Doctor speculates this is Bishop’s nature. To break out of Blackheath, Bishop will need to change his decisions so markedly that he has in effect changed his nature – become a different man.

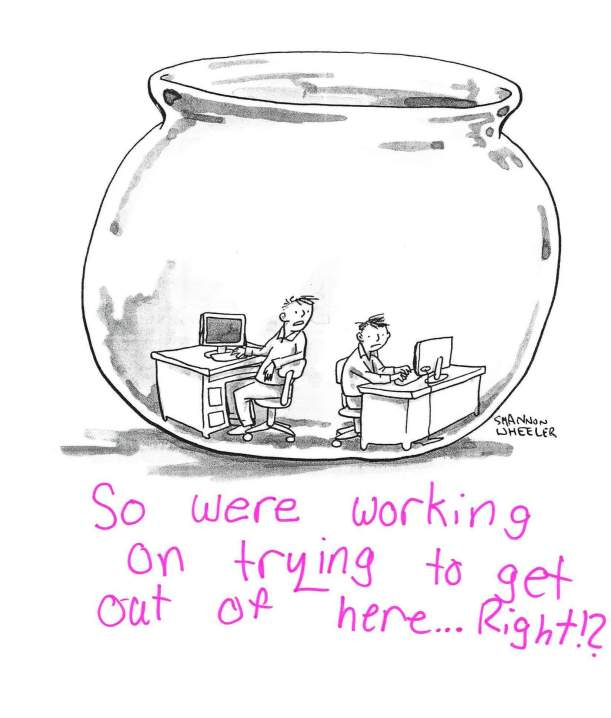

“[E]very man is in a cage of his own making,” proclaims the Plague Doctor.

This is a version of Hell.

The very name “Blackheath” summons a kind of hell: Blackheath south of the Thames in London, where thousands of plague dead lie buried (and where Blackheath Village is now a genteel suburb peopled by the kinds of upper-middleclass folk who enjoy Agatha Christie and will read this novel. I lived there myself for eight years). A “plague doctor” was a person who in the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries attended to plague victims, wearing “a beak-like mask which was filled with aromatic items. The masks were designed to protect them from putrid air, which (according to the miasmatic theory of disease) was seen as the cause of infection. […] These doctors rarely cured their patients; rather, they served to record a count of the number of people contaminated for demographic purposes.” [Wiki]

Blackheath has resonances of Limbo, from the Latin ‘Limbus’, meaning “edge’ or “boundary”, referring to the “edge” of Hell (ref Wiki). But the Roman Catholic religious concept ‘Limbo’ condemns those consigned there to eternity. Blackheath is more like a Purgatory, from which those destined to be saved will eventually be delivered.

More closely, Blackheath draws on the Hindu concept Samskara:

Sanskara (IAST: saṃskāra, sometimes spelled samskara)

In the context of karma theory, Sanskara are dispositions, character or behavioral traits, that exist as default from birth or prepared and perfected by a person over one’s lifetime, that exist as imprints on the subconscious according to various schools of Hindu philosophy such as the Yoga school.[3][5] These perfected or default imprints of karma within a person, influences that person’s nature, response and states of mind. – Wikipedia

Samskara is the repetition of behaviours that results in deeply entrenched behavioural patterns, in ruts, that effectively constrain our choices, determine our actions, and hence our outcomes: our karma.

To break Samskara, a concerted moral effort, an effort of courage, is required, and consistency.

The hell that is Blackheath is the hell of the addict, and more than one of Bishop’s host entities are addicted to drugs, alcohol, food, criminal, immoral or self-defeating behaviours.

The other guests at the masque ball at Blackheath are a Hieronymus Bosch representation of Hell, an evil cornucopia of vice. They are trapped in Samskara, doomed to repeat the same vile behaviours ad infinitum.

Yet the Plague Doctor tells Bishop he is different, “Each time you fail, we strip your memories and start the loop again, but you always find a way to hold onto something important, a clue if you will.”

The nature of the clue he wakes up to each new loop determines the tone, the nature, of that loop.

This loop, Bishop’s clue is “Anna”.

Bishop finds that with each successive host entity, the residual memories and traits of each host grow stronger. He first wakes as a man who is a blank slate, a man who can recall only the name “Anna”, and a vague sense that who he is, is a coward. His earliest hosts’ vices merely niggle at Bishop; his later hosts’ vices threaten to overwhelm him.

Each of Bishop’s hosts has different strengths and weaknesses, and he’s challenged to learn how to best use each one’s strengths, and best manage each one’s weaknesses.

He learns that masks, and being in different guises, only serve to reveal underlying character. Embodied in different entities, oftentimes he is only recognised by allies and prospective allies as Bishop because his behaviour contrasts with the way his host would have behaved.

At one point he tells a man with a differing philosophy, “We’re never more ourselves than when we think people aren’t watching, don’t you realise that?”

The other man argues back that Blackheath is a “puzzle, with disposable pieces”.

He argues that “Avoiding unpleasant acts doesn’t make a man good.”

The person killed today will reappear in endless tomorrows, to be killed again. Are they “never anything more than a trick of the light […]. Shadows cast on a wall”?

Are the characters that people Blackheath anything other than two-dimensional? Are they imbued with any real humanity? If not, does their fate matter? What is actually at stake?

The recurring time-loop that is the prison Blackheath is clearly a moral project, but what is its purpose?

The Plague Doctor provides a clue: “Do you know how you can tell if a monster’s fit to walk the earth again, Mr Bishop? […] You give them a day without consequences, and you watch what they do with it.”

Samskara

[MAJOR SPOILERS FROM HERE ON]

As well as being a moralist, Aiden Bishop is a romantic.

When the Blackheath puzzle ends, he believes in a future he must know is impossible:

“It seems like a dream, too much to hope for […]. The luxury of waking up in the same bed two days in a row, or being able to reach the next village should I choose. The luxury of sunshine. The luxury of honesty. The luxury of living a life without a murder at the end of it.”

This, despite the Plague Doctor warning him, “Once you’re released, start running and don’t stop. That’s your only chance.”

Despite that he has no knowledge of the life he’ll be returned to – to what point in Bishop’s timeline, into what practical reality. What paperwork do citizens require? How is ID established? Will irises be read, faces mapped, fingerprints scanned? How is food and shelter obtained? Income acquired? Transport accessed?

Don’t get out of the carriage.

Seems to me there is death at the end of this road. In effect, the footman still awaits.

Aiden Bishop, who was finally able to combine the multiple perspectives and talents of eight different hosts to make sense of what happened in Blackheath, appears, in his haste to shed everything he learned at Blackheath, to have fallen once again into the pit dug by the dominant trait of his nature: that is, the rut of his obstinate tunnel vision.

Whatever happens next is karma.

Yet Bishop is a delirious optimist:

“Tomorrow can be whatever I want it to be […]. Instead of being something to fear, it can be a promise I make myself. A chance to be braver or kinder, to make what was wrong right. To be better than I am today.”

*Or maybe you only think you know.