Blood & Beauty / In the Name of the Family – Sarah Dunant

The White Princess – Philippa Gregory

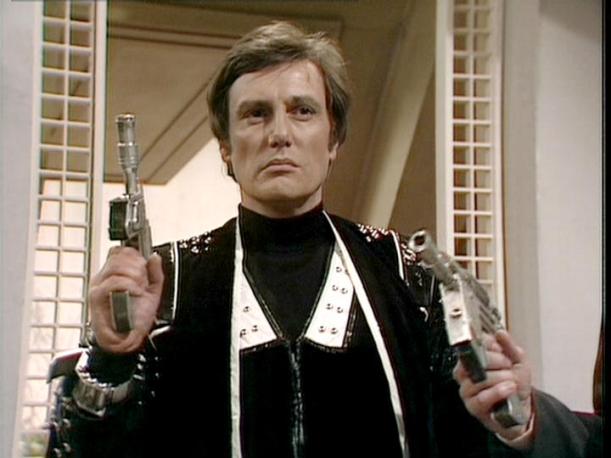

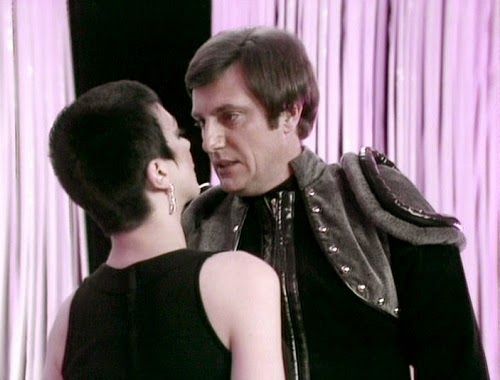

Game of Thrones (TV series) – George R.R. Martin, David Benioff, D.B. Weiss

Lucrezia Borgia lived an extraordinary life, but really, who’d swap? Who’d be a Renaissance princess for real?

Born in 1480, the illegitimate daughter of a prince of the Roman Catholic Church, Pope Alexander VI, Lucrezia was twice engaged before age 12; married (to a third fiancé) at 13, divorced four years later, allegedly (but implausibly) still virginal; remarried at 18, widowed by age 20 when her brother had her husband garrotted; married once more at 22, to a duke’s syphilitic son; ten children (and multiple miscarriages) later, dead at 39. Libelled through the centuries as an adulteress, an incestuous wanton, a poisoner.

There’s Elizabeth of York, born in 1466, eldest daughter of King Edward IV of England: first engaged at age 3; then engaged to the French Dauphin at age 9; rumoured to be her uncle King Richard III’s intended wife at 18; offered by her malformed uncle to the Portuguese king’s heir; offered by her mother to Henry Tudor, King Henry VII. Six live births, three surviving children (including the future Henry VIII) when she died in childbirth on her 37th birthday.

Then there’s Sansa Stark. Sansa Stark is a fictional character. Arguably, she’s a composite invention, with elements of Elizabeth of York’s life woven through her story, and a few tangential elements of Lucrezia Borgia’s: Lucrezia’s sister-in-law, from her second marriage, was named Sancia. Viewers of the TV series Game of Thrones will recall that Sansa was engaged to King Robert Baratheon’s heir Joffrey, then married to the dwarf Tyrion Lannister, abandoned still virginal to be bigamously married off to the sociopathic rapist Ramsay Bolton. (Readers of the George RR Martin novels A Song of Ice and Fire understand the narrative in the books unfolds somewhat differently.)

What’s interesting about these storylines is agency.

Were Lucrezia and Elizabeth merely marriage pawns? Were they merely bargaining chips in high stakes political alliances? Or did they have some say in their ‘choices’? Once married, what degree of ‘choice’ did they have in how those marriages – and those political alliances – worked out?

Any historical fiction is always a working through of issues that address contemporary readers. As is all science fiction. So fictionalised imaginings of the lives of Lucrezia Borgia and Elizabeth of York, and fictional creations such as Sansa Stark, are vehicles to explore issues affecting women today: self-determination, autonomy and dependence among them.

Sarah Dunant has written five novels now which explore aspects of women’s lives in Renaissance Italian states. The Birth of Venus (2003) tells the tale of a Florentine merchant’s daughter who aspires to be an artist. In the Company of the Courtesan (2006) follows the career of a courtesan who, after the 1527 Sack of Rome by French armies, rebuilds her career in Venice. Sacred Hearts (2008) concerns a young girl unwillingly interned in a convent as a novice nun. Blood & Beauty (2013) and In the Name of the Family (2017) recount the fortunes of Lucrezia Borgia, through to the death of her father and her brother Cesare’s political demise.

Sarah Dunant scrupulously follows historical fact as best it can be ascertained. Where there is no surviving primary evidence, she chooses plausible speculations, from a feminist perspective. Most of the calumnies against Lucrezia Borgia are not plausible. Consequently, the Lucrezia Borgia Dunant presents is much the Lucrezia Borgia presented by Sarah Bradford in her readable biography, Lucrezia Borgia: Life, Love, and Death in Renaissance Italy (2004) – an exemplary Renaissance princess, a convent-educated patron of the arts well-versed in diplomatic skills.

This Lucrezia Borgia has no say in her first marriage and divorce, no hand in the death of her second husband, no choice in leaving her first-born child, but is actively involved in negotiating her third marriage and committed to ensuring that marriage succeeds. She is not an adulteress, being instead a poet’s muse, in line with poet-patroness conventions of the day. Dunant doesn’t allude to Lucrezia’s alleged affair with her brother-in-law the Duke of Mantua, but the case is well-made for why a canny political operative such as Lucrezia proved to be would reject a sexual liaison. (Besides, Francesco Gonzaga was frequently incapacitated by syphilis, and there were few occasions when the two were in physical proximity; their relationship was mainly a written correspondence.)

Lucrezia couldn’t prevent a husband she apparently loved from being murdered on her brother’s orders and was obliged to collaborate in impregnation after impregnation by a husband with advanced syphilis whose temperament and affinities were poles apart from hers. But their interests coincided: preserving the duchy of Ferrara for d’Este rule in a time of turmoil. As a team, they were a success.

Similarly, Elizabeth of York and Henry VII appear to have made a success of their marital alliance, albeit on very different terms. Elizabeth’s claim to the throne of England, as the eldest surviving child of Edward IV, was better than Henry Tudor’s. (Being female did not disbar her, as the subsequent ascents of Mary I, Lady Jane Grey and Elizabeth I in the Tudor period proved.) It was important to Henry that it be clear he claimed the throne in his own right, by right of conquest, and not as male spouse to a queen regnant, the Yorkist heir. The timing of his coronation, prior to the marriage, reinforced this point. Elizabeth was relegated to queen consort, stripped of political power.

It wasn’t that late medieval English female royals had no formal political influence, as had been argued until relatively recently. Henry’s mother, Margaret Beaufort, was his foremost political adviser, with private rooms adjoining her son’s and prominence in public ceremonies. Her household papers attest to the degree of power and autonomy she enjoyed.

But Elizabeth, the White Rose of York, was acknowledged as little more than a breeder. Little contemporary testimony as to her character and activities survives, other than that she was a most amiable woman, with a russet gown and one blue, fond of past-times such as cards, music and dancing, who loved her siblings, her mother and her children, and also her greyhounds. She grew plump over time. Her son Henry, who was 11 when she died, remembered her as a very pretty woman. She lived away from the public gaze, mostly at Greenwich Palace and Eltham Palace.

For Elizabeth, this was a good outcome. She had grown up as the marital prize for the would-be kings. Her destiny was to be queen of England, and she fulfilled that destiny. Even if she could not exercise power herself, her son would be king, and her descendants future rulers. She survived the downfall of her house, the House of York, the York Plantagenets, just as Lucrezia survived the fall of the house of Borgia to thrive as duchess of Ferrara, mother of future dukes.

Both were survivors – until they weren’t, until childbirth felled them. But they survived their brothers and fathers, and fared better than many might have wagered at the time.

The central mystery of Elizabeth’s life however remains what she made of the emergence of the man who claimed he was her brother Richard – a man who claimed he hadn’t been murdered in the Tower of London as believed, had survived his older brother Edward, had been brought up in Burgundy, and was in fact the rightful king of England, King Richard IV. This man was supported by European royalty and enjoyed prolonged hospitality at royal courts, marrying the daughter of one of Scotland’s most powerful nobles.

When this man proclaimed himself king in England, he hoped for a popular uprising. It didn’t happen. Instead he was captured. Henry VII’s agents denounced him as an imposter. They said he was really Perkin Warbeck, a Fleming. But Henry treated the imposter well initially, allowing him to live at court for 18 months, albeit under guard and without his wife, who lived under the protection of the queen, Elizabeth.

It is improbable, but possible, that Perkin was born Richard. Did Elizabeth believe Perkin Warbeck was a pretender? Was she unsure, confused? Or, privately, did she recognise him as her brother? Did she believe his wife Lady Katherine was her sister-in-law, or was Lady Katherine, for her, another young noblewoman married for political purposes? Did Elizabeth ever get to have close contact with Perkin? Did she get to see him, to speak to him, at all?

Perkin Warbeck was recaptured after allegedly trying to escape. He was severely beaten and dragged on a wooden hurdle to execution at Tyburn, alongside Elizabeth’s cousin, her aunt Isabelle’s son Edward, the young Earl of Warwick. How did this impact Elizabeth?

The truth is, Elizabeth the White Rose of York, queen consort of England, had zero agency to affect Perkin Warbeck’s fate. Even if Perkin Warbeck was Richard Plantagenet, rightful king of England, and even had his sister recognised him at first glance, there was not a thing she could have done to avert his end. Any hint of recognition, distress or mourning would have been anathema to her husband and to the dynastic interests of her children, and might have endangered Elizabeth herself. After all, her husband – and, after her death, her son Henry – spent years systematically destroying any kin of Elizabeth’s who could be acclaimed as Plantagenet heirs.

I’m not a huge fan of Philippa Gregory’s novels, despite their immense popularity. But Elizabeth’s powerlessness is poignant as depicted in The White Princess, just as Lucrezia’s powerlessness to prevent her second husband’s murder is poignant – is shocking – as depicted in Dunant’s Blood & Beauty.

Philippa Gregory represents Elizabeth of York almost as catatonic, as paralysed, in relation to Perkin Warbeck. Dunant shows Lucrezia and her sister-in-law Sancia desperately attempting to save Alfonso of Aragon by appealing to a higher authority, her father, the Pope – only to inadvertently leave him exposed and fatally vulnerable.

On Game of Thrones, as at the time of writing we don’t know where Sansa Stark’s story is headed. She’s developed from being a naïve ingénue through manifold manipulations to her current status as an avenging Amazon, intent on reclaiming what is hers. So far, all but one of her immediate family have been killed (with one resurrected, and one transformed into a three-eyed crow). I don’t know whether Sansa gets to call the shots in her future. But I’m betting she doesn’t die in childbirth.

Sansa, of course, is a fiction.

https://ellymcdonaldwriter.com/category/medieval-history/

Shieldwall is a welcome surprise. It’s a serious – and successful – attempt at telling the hero tale of Godwin, father of Harold, last Anglo-Saxon king of England, in a style that’s consciously, but not crudely, an homage to the genre of Germanic heroic lay. It’s elegiac, lyrical, grand, high-minded; centrally concerned with honour and male friendship, fathers and sons, duty, war and death.

Shieldwall is a welcome surprise. It’s a serious – and successful – attempt at telling the hero tale of Godwin, father of Harold, last Anglo-Saxon king of England, in a style that’s consciously, but not crudely, an homage to the genre of Germanic heroic lay. It’s elegiac, lyrical, grand, high-minded; centrally concerned with honour and male friendship, fathers and sons, duty, war and death.