Monsieur Mayonnaise: Philippe Mora’s colour-saturated documentary/memoir/graphic novel/cartoon about how his parents Georges and Mirka survived the Holocaust to introduce European bohemian culture to post-War Melbourne, Australia.

And how Gunther Morawski became Georges Morand then Mora then Monsieur Mayonnaise then Georges Mora; or, how Gunther Morawski became a Resistance hero, father substitute to Jewish war orphans, people smuggler, and impersonator of Catholic nuns (in company with best mate Marcel Marceau).

Some of my responses:- with apologies to Philippe Mora and his family for details I’ve recalled wrongly or that should have been included but are not. I hope the Mora family will forgive me for borrowing some of their images and artwork for this blog.

[SPOILER ALERT: If you plan to see Monsieur Mayonnaise this response might be best read AFTER viewing. On the other hand, it’s the Holocaust – you know how that unfolded. Don’t you?]

Artwork by Philippe Mora for his graphic novel Monsieur Mayonnaise

One morning Leon Zelik left his Paris apartment to buy a newspaper. While he was out, soldiers arrived and took his wife and his three daughters, Mirka, Madeleine and Salome.

The women were herded onto a train along with 1000 other Jews, mostly women and children. They were terrified. As the train rattled along, Mme Zelik and Mirka, her eldest daughter, peered through the wooden slats of their crate-carriage, strained to identify signage at train stations they passed.

The mother had had the presence of mind to grab a sheet of paper, a pen and an envelope from their apartment as they were taken. Now, she wrote the names of each train station in sequence. She folded the page into the unstamped envelope, which she addressed to her husband, Leon Zelik, at their street address.

She directed Mirka to drop the sealed envelope through the crate cracks as the train slowed. Mirka was frightened it would blow back onto the tracks.

They were disembarked at a massive holding centre. Four days before their contingent were scheduled to be shunted to Auschwitz, guards came and released them. As Mirka looked back towards the camp she saw the other detainees crowded against the fences, the children big-eyed, watching the Zelik family retreat to freedom.

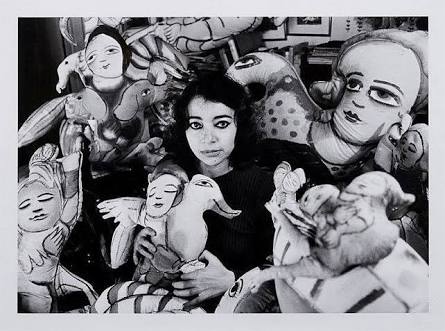

In later years Mirka said the big eyes in the faces of the doomed children were the genesis of the angel children she painted throughout her life. She said the guilt pained her. Telling this, she cried.

Someone had found the addressed envelope, stamped it, and mailed it to Leon in Paris. From the list of train stations, Leon worked out the camp where his family were held. He convinced a clothing manufacturer to request that the Zelik women be released on the grounds that the mother was a required worker manufacturing German army uniforms. A lie, but it worked.

In later years, Mirka thanked that anonymous person who found her mother’s letter, every day, life long.

Mme Zelik, Mirka, Madeleine and Salome were the only survivors of the Jewish detainees on that transport. I have/had a mental blank on The Mother’s name. Wiki says she’s “Celia (Suzanne)” but in his film Philippe Mora refers to her by what I think must be a Lithuanian petname or diminutive.

Mirka Mora with angel children

There’s a sequel: by chance Leon met a French farm worker, a Christian, who offered the Zelik family sanctuary. In his village was a house locked up while its owner was a prisoner of war. The Zeliks spent 2 1/2 years there. The Frenchman’s daughter says her father never questioned that providing sanctuary was the right – the only – thing to do.

I won’t recount Georges story here. I can’t get his story out of my mind, and have been telling it to almost everyone I meet. But every time I tell it, I cry, and the people I tell it to cry too.

Suffice to say there’s a 92 y.o man on film who says he became an eminent New York child psychiatrist because Mora and his Resistance colleagues saved his life, because Mora cared, and because he wanted to be like Mora: to save children. Even if it meant dressing up as a nun and trekking Jewish war orphans to the Swiss frontier, a la The Sound of Music. In company with the famous mime Marcel Marceau. (No, even in New York none of this is required of child psychiatrists. This is what French Resistance operative code-name Mora did.)

Georges Mora clips his son Philippe’s hair

In Philippe Mora’s film he visits a museum memorializing child victims of the Holocaust deported from France (not the famous Holocaust Museum in the States – I googled but could not identify this museum). The interior walls seem to be lit with a low golden glow and have what appear to be timber vertical divides and, less prominent, horizontal divides, so that the walls suggest a panel of spaces for portraits or icons. Many of the spaces are filled by photographs of children who died, with their name and (I think) age. The spaces left empty are ones where no photograph has been located. I believe in this museum there are 6000 framed spaces.

Aesthetically it’s beautiful. Emotionally, it’s devastating.

Artwork by Philippe Mora for his graphic novel Monsieur Mayonnaise

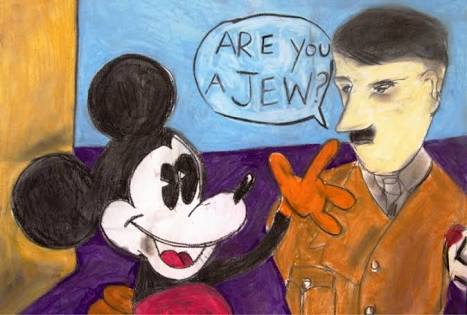

My father shocked me today when he asked if pogroms predated Hitler. He seemed to think anti-Semitism started in post-WW1 Germany. I can only think this is cognitive slippage in old age and illness, as Dad, having been a child in the ’30s, went on to be a student of economics, politics and modern history.

Yet knowledge of modern history is vanishing, replaced by Hollywood distortions (Inglourious Basterds), denial, and a galloping cynicism that buys into conspiracy theories and a belief that everything we’ve been told is propaganda.

When I was 22, in 1983, I went to an adult education course where my classmates included 3 older women, post-WW2 Jewish refugees. Two spoke with heavy accents and the third, after 35 years in Australia, barely spoke English at all. Her friends explained she rarely ventured outside the Jewish emigre community.

I asked if they’d encountered anti-Semitism in their early years in Australia.

“Oh darling,” one woman laughed. “No. People here didn’t know what a Jew WAS.”

I suppose part of the problem is when we can’t admit our ignorance, and *think* we “know” the stranger.

Openness to learn is more important than ever. But in a media age, what media do we trust?

George Mora. Monsieur Mayonnaise.

My friend Donna says, “I was married into a Jewish family for 32 years. The matriarch pulled the address labels off of every magazine that came to the house (the goyim see the name and know that is a Jewish household), and no one talked about illnesses or diseases except in very hushed voices (the government takes the weak first)… that was not uncommon in the WWII generation, but they are slowly dying off, and the younger folks have no idea..”

“George Mora’s” two sons had no idea he was really Gunther Morawitz, German-born, medical student at Leipzig University, native German speaker, until his last years; and no idea why he wouldn’t step into a VW or Mercedes-Benz or use Krupp appliances.

When I was at school I had teachers who were Holocaust survivors. Exposure to first-hand witnesses is invaluable. We’re losing them.

Remembering snow (1986)

Rosa says

I remember snow

When I was a girl I lived

in Siberia

There was so much snow so

much

we skated on a river of ice

Mrs Cameron

born Roth

40,916: tattooed in blue

teaches art

forgets

she remembers.

Don’t ask.

But

Mrs Zabukovec

gypsy eyes

teaches German

born Bulgarian

she remembers

being 18

in Berlin

being 18

Russians

she remembers.

Don’t.

She remembers

long rows of blossoms, white-clustered blossoms

so white so

much breaks

down

remembering snow