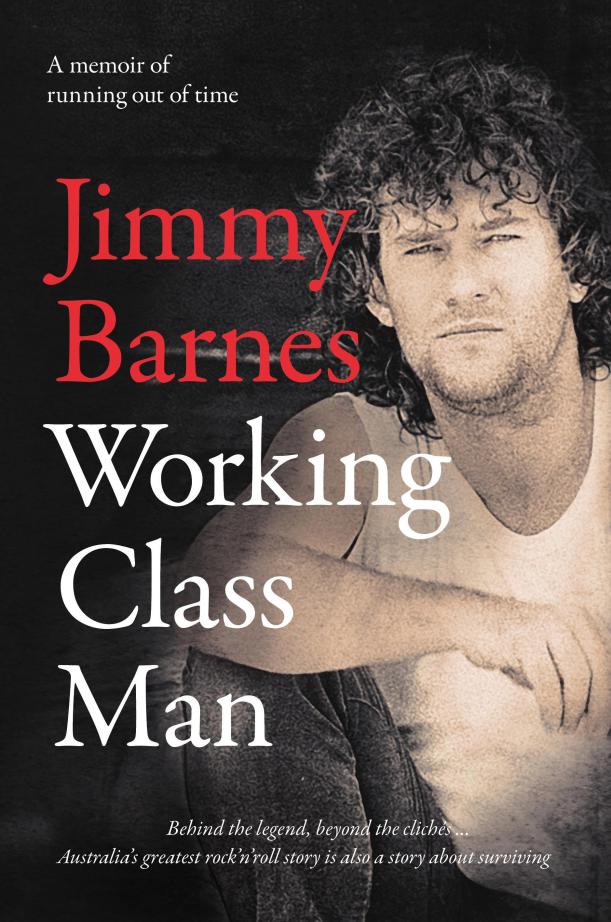

Working Class Man by Jimmy Barnes (Harper Collins 2017)

Working Class Boy by Jimmy Barnes (Harper Collins 2016)

A boy and a girl are seated on the top step of a flight of stairs in a grand old house. She is 19, he’s five years older, almost to the day. Their knees are touching.

He leans close towards her and says, “You’re a killer.”

She is dismayed. “A killer?”

His turn to be taken aback. “It’s a compliment,” he reassures her. “A killer. I think you’re fantastic.”

The girl adores him. She still adores him 37 years later, even though she’s barely seen or spoken to him since December 1983. A chance meeting on a Kings Cross street in 1985, a moment backstage in 1991, a note in about 2001, another moment backstage in 2007, then a book signing in St Kilda in 2017.

The boy is Jimmy Barnes, known and loved these days as an Australian rock music icon both as a solo artist and as lead singer in the band Cold Chisel. The girl is me, and the book Jim autographed for me at a book signing yesterday is Working Class Man, his second volume of autobiography, following his memoirs of a brutal childhood, Working Class Boy.

Working Class Boy is a gut-wrenching account of a childhood filled with neglect and violence, of a young boy struggling to survive a dysfunctional Glaswegian Scot family who migrated to Australia in 1961 and moved around Adelaide’s tougher, working class suburbs. It is compelling reading, beautifully written, with a fluency, passion and wit that surprises me not at all from the Jimmy Barnes I knew. The voice is authentic. I could hear him speaking in the written words.

I loved every page, every paragraph, of Working Class Boy. Yes, some parts horrified me. Some made me cry. Some helped me understand things we had (and have) in common I hadn’t understood before.

I was born in 1961. My family moved to Adelaide in 1963. We lived in what’s known as the “leafy green suburbs”, the pleasant suburbs housing the professional classes. We lived at the base of the foothills overlooking the plain Adelaide fills, in a place called Glen Osmond, just up the road from the Arkaba Hotel, where Jim and his brother John roomed for a time as young adults.

My dad had Scottish heritage – his name was Donald Angus McDonald – and my great-grandparents were Gaelic speakers. They came from south-west Scotland, and/or from the isles. Some of them were very probably Irish migrants to south-west Scotland, like Jim’s folk. Some of them were Irish from County Galway, the heart of the bilingual Gaeltacht. As best I can tell, they were all heavy drinkers.

Although my father grew up in a nouveau riche mini-castle and his father was a big man in his country town, a self-made man with a successful business, my father grew up with family violence. He very seldom alluded to it. It was only when he was dying, earlier this year, that in his last weeks he fleshed out a little of the kind of violence he witnessed between his parents. Within our family we’d all always known there was something dark and frightening, some things unexplained, but we’d never heard details. It was painful.

Hearing my father recount in plain terms what he’d been subjected to as a child helped me understand some of my dad’s own more erratic behaviour, and his drinking. I could also clearly see, reading Jim’s book, more reasons my teenage self felt an affinity with Jimmy Barnes: if I wrote a list of my dad’s best qualities, and his worse, then wrote a list of Jimmy’s best and worst qualities as I saw them, the lists would be identical. They were cut from the same cloth.

As soon as I finished reading Working Class Boy, I posted on Facebook:

Belatedly, I’ve finally read Jimmy Barnes’ memoir of his childhood, Working Class Boy, a remarkable work. On a personal level, there was so much in the voice, the reflections, the humour, the insights, the choices, the LANGUAGE that brought the Jim I once knew present. Which was a pleasure for me.

On a writerly level, I am blown away. Writing a coherent narrative takes skill. No surprise Jim is a great story teller. No surprise he’s articulate and rock-my-socks-off intelligent. But writing skills come through practice. I hadn’t realised he was so practiced. (Two previous attempts totaling c.60,000 words before a 100,000 dam-burst.)

Writing dialogue takes a great ear. Jim has that. In spades.

On a wisdom level – I always knew Jim as super-astute, with an off the charts EQ, but the maturity he demonstrates here through his writing has me worried. I’m only five years younger. Can I get that wise, so soon?

Jim’s wisdom is hard won. I would not wish to travel the road he has to acquire it. God bless him.

I am so eager now to read the follow-up, Working Class Man. This will be where I start to recognise more people, places, situations. I did meet Jim’s mum, his sister Linda and his brother John [also his siblings Alan and Dorothy, in passing], but I didn’t get to know them; arguably a lot of the people I met in the next stage of Jim’s life are also people I never truly ‘knew’, but we did share experiences and we share witness.

I knew Working Class Man would cover the period when I knew Cold Chisel – the band’s last four years, the height of their success and their ferocious last year or two – and there was so much I never understood about what went down, what happened between specific individuals, why they behaved the ways they did across that time. I wanted to understand, because I felt I’d been part of the emotional turmoil, that it affected me, and it had blindsided me.

And now I have read Working Class Man.

Early in the tale I meet friends we had in common, when Jim and I both still lived in Adelaide, moving in different circles but, in Adelaide, a large country town with zero degrees of separation, interconnected.

We share some history, this town and I

And I can’t stop that long forgotten feeling…

(Flame Trees – lyrics Don Walker)

Here on the pages is my friend Vince Lovegrove, Cold Chisel’s first manager, and his wife Helen. Helen taught me to go-go dance when I was six or seven. She was a nurse with a close-knit group of bff’s including Mary, one of my earliest babysitters, who became one of our family’s dearest friends. Through Mary I knew Helen and through Helen I met Vince.

Vince when I met him was a minor pop star, sharing vocals in a band called The Valentines with a cheeky singer called Bon Scott. Bon Scott went on to sing with an Adelaide band called Fraternity, later fronted by Jim Barnes (with his brother John on drums), while Bon went on to front AC/DC. That’s Adelaide for you: the city of churches and serial killers, the town that spawned Bon Scott , Vince Lovegrove, Cold Chisel – and, less remarkably, me.

This is a review – or more correctly, a response – to Jimmy Barnes’ books Working Class Boy and Working Class Man. For a few years there his story and mine dovetail, so forgive me indulging in “sentimental bullshit”, settling in to play “Do you remember so and so?”, as Cold Chisel’s principle songwriter Don Walker put it in his lyrics to Flame Trees:

I’m happy just to sit here at a table with old friends

and see which one of us can tell the biggest lies

I first met Jim Barnes in Melbourne. He was standing at the edge of a stage in a St Kilda venue, alongside his bandmate Don Walker, staring down at me. I was staring up, in my Anne of Green Gables floral-sprigged mauve frock, my hair the straggling remains of a dropped-out perm, my chubby upper arms straining at the cuffs of short puffed sleeves.

“Who’s in this band?” I demanded.

I was enrolled in Law/Arts at Monash University, then considered a second-tier suburban university, an offer I’d taken up over the offer from the more prestigious Melbourne University Law School due to some forlorn desire to be just a regular suburban girl. I wasn’t succeeding. I was a misfit, and I spent my days smoking dope and spinning the turnstile at the student radio station, 3MU.

3MU had lined up an interview with Jim and Don’s band Cold Chisel. Except no one owned having set up the interview and no one wanted to conduct an interview. I volunteered. Now here I was standing beneath a stage during a sound check.

The next time Cold Chisel came to Melbourne I interviewed Don and Cold Chisel drummer Steve Prestwich in their hotel room in St Kilda. I wrote it up as an article for the Adelaide-based rock magazine, Roadrunner.

In the hotel room, Don Walker considered me as if I were brain-gym puzzle. I asked Don what he was thinking.

“I’m wondering what social background you come from,” he said.

I told him my father was a director of a household name corporation and my mother was an academic. His mother was an academic too, but Don didn’t mention that.

The band put my name on the free list at the door to see them play one of Melbourne’s big beer-barn suburban venues, and at Don Walker’s invitation I joined them in the band room after the show. It was the tail end of Chisel’s 1979 Set Fire To The Town tour, promoting Cold Chisel’s second album, Breakfast at Sweethearts. The band joked it should be called the Let’s Get Fat tour. Sure enough, Jim did not look well. He was puffy, unshaven, his eyes were glazed, his skin a bad colour, smeared with a greasy sheen, and he was out of it, off his face on god knows what. He nodded bleary-eyed recognition to me.

When Jim was functioning, which seemed to me most of the time, he was funny and bright and kind. Over the next year, after I moved to Sydney and started writing regularly for RAM (Rock Australia Magazine), I saw a lot of him. Briefly, he shared a house with Vince Lovegrove, just around the corner from my place. Then he moved into that grand old house where we sat together at the top of the stairs, also not more than a few minutes walk from my small flat. Bandmates referred to that house as “Jim’s castle”, which puts me in mind of the grand country house my dad grew up in.

Jim and I both lived in Paddington, an inner-city Sydney suburb then in the process of gentrification. Boundary Road formed the boundary between Paddington and Sydney’s red light district Kings Cross. In those days I alternated between dressing in jeans and flannel shirts and dressing in what might kindly be described as outdoor lingerie. It wasn’t uncommon for hoons visiting Kings Cross from the outer suburbs to pick up prostitutes or bash trans people to mistake me for a hooker. Sometimes they were menacing. One time I was pursued: I ran, but they ran faster. I knew the short cuts and ducked down a hidden through-walk. I knew I couldn’t make it to my own home before they spotted where I’d gone, so I ran through the wrought iron gates to Jim’s grand house and hid in the portico by his front door. I watched these boys trying to track where I’d gone. They sniffed around like hellhounds then finally gave up. My heart was pounding.

Jim and his housemates were out at the time. That night I told him the newspaper headlines would not have looked good: ‘Girl raped on rock star’s doorstep.’

Jim grinned and shot back, ‘While rock star at the beach!’

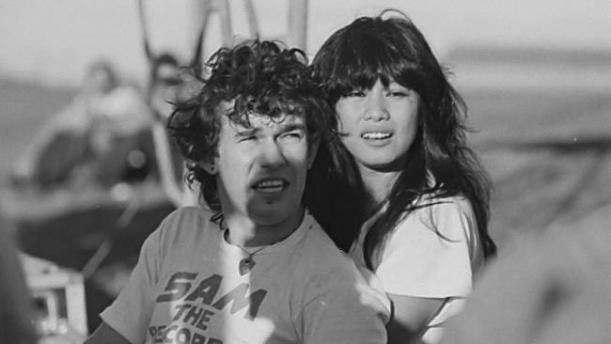

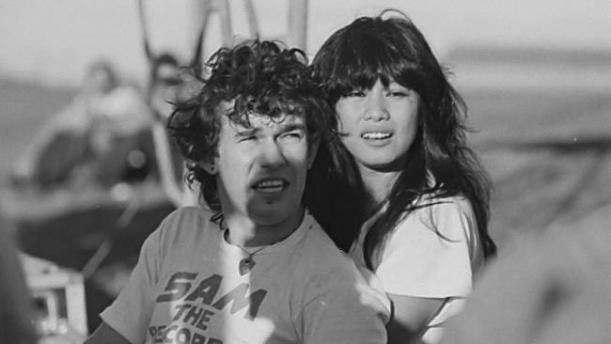

Elly in 1983, the year Cold Chisel split

When I first met Chisel I was a fat teen with binge eating disorder, post-anorexic. As one venue promoter correctly surmised, you could write my sexual history on the head of a pin. The surfers, apprentice plumbers and neophyte heroin addicts my popular older sister hung out with had zero interest in me. Being seen with a fat chick was an embarrassment.

So when Don Walker referred to me, approvingly, as an “earth mother”, I failed to hear the compliment and was mortified. When I walked through Kings Cross and saw a porn mag titled Deviations featuring a special issue on fat chicks, my immediate thought was: “That’s me. I’m a sexual deviation.” (My eating disorder did my friendship with Don no favours. I had it in my head that Don only liked thin women, and, since I valued Don’s good opinion, that meant that whenever I felt self-conscious I’d get defensive, even semi-hostile, around him.)

When Jimmy Barnes told me I “looked the way a woman should look”, it was the first time I’d heard male affirmation.

More important, and certainly more intimate: Jim taught me how to punch.

Jim met and fell in love with Jane, the woman he married, not long after we met. But his relationship with Jane was turbulent. He did a lot of drugs. He drank a lot. When I complained I didn’t have money to buy groceries, Jimmy told me I could live on speed and booze. He must have liked that line, because he repeats it in Working Class Man. I didn’t have Jim’s constitution. I couldn’t afford groceries so I lost weight. Men started taking more sexual interest in me. I stayed cautious.

At Vince’s house, the lead singer of a young support band tried, politely, to chat me up. I was so unused to being chatted up and I couldn’t deal. I flung helpless looks towards Jim. He laughed.

Jimmy Barnes with Vince Lovegrove and Vince and Helen’s daughter Holly, Jane’s sister Jep Mahoney at front

Jim writes of Cold Chisel in Working Class Man that “These four guys would eventually become my family. The family I always needed.” With much less cause, I too regarded Cold Chisel as family. Although my birth family, living in Melbourne, were nowhere near as explosive as Jim’s birth family was, as a family unit we were not, across those years, in good shape. My father accused me years later of choosing to live first interstate then overseas in order to be far away from my family. He was not wrong, though it hurt me to admit it.

For me, Cold Chisel were the big brothers I never had.

Jim could be protective. There was a night when white powders were being passed around and when I reached for my turn, Jim slapped my hand.

“Not that! That’s smack,” he warned me, sharply.

The huge breakthrough album for Cold Chisel was East, released May 1980. Before it came out I watched Chisel rehearse for the album tour and I remember I was irritable. I recall Jim being unimpressed when I criticised the harmonies on Twist’n’Shout, so maybe that was it.

In the train on the way back to Kings Cross with Don Walker and Don’s partner, the rock writer Jenny Hunter-Brown, I remember Don looking at me like I was a toddler in need of a pacifier and handing me a Walkman, a small cassette player with mini-headphones.

“Here,” he said. “Listen to this.”

It was East, the first track: Standing On The Outside. I was so shocked by how slick and tuneful those first bars sounded, but I didn’t want to let go of being grumpy and give Don the thumbs up. I listened with a stiff face to the whole track, then took the earphones out.

“What do you think?” Don asked.

I think I said, “It’s good. It’s very good.”

In Working Class Man, Jimmy writes that when Don presented Standing On the Outside to the band,

“I felt like I was singing a song that came from somewhere deep inside my soul. I had been standing on the outside all my life, never being allowed to taste or touch the world that was just outside my reach.”

Jim writes that on East, Don “came up with a lot of songs about outsiders. We were outsiders, and we were surrounded by outsiders and misfits. There was something about the outcasts from society that fascinated him. Maybe that’s why he liked me.”

Me too. Maybe that’s why Don liked me when he met me, too.

Jim asked me which of the songs from the East live playlist I liked best. I told him Tomorrow (the set opener) and Star Hotel.

Jimmy met my eyes: “Me too”, he said.

In Working Class Man he writes, “Star Hotel let me sing about not being good enough, not being wanted or worth anything, and wanting to tear down the world because of it.”

Until I read that line I didn’t realise this was the “me too” we shared. I came from a relatively privileged background, Jim came from what is sanitised as “disadvantage”. But we both had a fundamental sense of being worthless, and a desperate fear of being abandoned. We both had deep wells of anger and terror.

When Jim writes in Working Class Man about near hysteria at the prospect of being separated from Jane when she fell ill in America, I cried:

“The idea of being separated from Jane again made me feel sick. I couldn’t lose her. If I let her go now I might never see her again. I always had the feeling that I would end up alone. I didn’t deserve her. I couldn’t let her go. […] I was definitely hysterical now. I was crying.”

That is so precisely how I felt about being part of Chisel’s circle. I was terrified of being expelled. I felt that Jane didn’t like me, and I can’t blame her. At my fattest I once trod on her while wearing stilettoes. But not to make light of this (so to speak): it was not easy for Jane being married to Jim. Even then, there were so many hangers-on pressing for Jimmy’s time and attention, and some had no scruples about how to achieve that end. There were individuals hanging out with Chisel who Jane disliked and mistrusted, mostly with good reason. I didn’t try to see things from her perspective. I resented her for seemingly separating Jim from people who had been his friends – for separating him from me.

I hated watching Jim cease to be my friend, and I was beyond terrified to lose my friendship with Don, for much the same reasons Jim and the band valued him: because Don was the big brother of big brothers, the stable one, the calm, capable, trustworthy one, the one who made sure what needed to get done always did get done. What a burden Don shouldered.

Cold Chisel, with Don Walker at centre

After I spoke with Jimmy at the book signing this week, I spoke with Jane. I leaned in close and said, “Thank you for keeping him alive.”

Jane instinctively pushed back, saying “It wasn’t me.”

“I know,” I replied. “He did that. But you both did that. You did it together.”

She half-nodded, warily. I know better than to put the burden of someone’s survival, of someone’s thriving, onto their partner. I asked if I could hug her. She wasn’t keen.

“After 30 years…” she began. I hugged her anyway.

I was over-emotional, and it’s not right to force another person’s emotional space. But for years I’ve recognised I was wrong about Jane. Jim ceased to be my friend after he and Jane married and committed to a life together, but Jane was and is, it seems to me, very likely the best thing that’s happened to Jimmy Barnes.

“You made his life,” I whispered, as I hugged her.

Years after Jimmy left Cold Chisel, years after Cold Chisel broke up, I was living in London. It came to my attention Vince Lovegrove was living in London too. I made contact and we talked on the phone.

Vince told me he’d worked with Jim when Jimmy Barnes toured Europe, and that Jim had not been in a good place.

“He’s a mess,” Vince told me. “He is drugging and fucking around and he’s filled with self-loathing. He can’t bear to look at the man in the mirror.”

This was not long after Michael Hutchence’s death and I was filled with fear that, like the INXS frontman, Jim might kill himself, intentionally or otherwise. I was in denial. I was angry at Vince for being the bearer of bad news, and for a moment – a long moment – I believed he was exaggerating the mess that was Jimmy Barnes because he was jealous of how much Jimmy meant to me, and because by exaggerating the depths of Jimmy’s personal decline it might distract from his own decline. This long moment – this extended denial – contributed to me not following up the plans Vince and I made to meet up.

I regret that now. Vince was killed in a car crash in early 2012. Friends are valuable. Friends don’t cease to matter because years have passed.

Do you know I reach to you

from later times…

(Letter to Alan, lyrics by Don Walker)

I now know, after reading Jimmy’s account of his solo career and life across the years when we didn’t see each other, that Vince was not exaggerating. I now know that Jim very nearly did kill himself, in circumstances not unlike the circumstances in which Michael Hutchence died.

I am profoundly grateful my friend is alive.

I am profoundly grateful he wrote this harrowing book, painful as it’s been for me to read. I am grateful to his family and the friends who love him, who have been by his side.

I know Jimmy Barnes didn’t write this book so that people he wouldn’t recognise in the street could reminisce 35 years later about their brushes with fame. Seems to me he wrote it for himself, yes, as therapy; and also for the people who he loves, the people he perhaps feels he owes explanations; for people who are children of family violence, children of alcoholics and addicts; and for the people who share experiences similar to his of addiction, self-loathing, the fear of abandonment, the terror of loss.

When Jimmy was a child, he used to run away from his family, all the way down to Glenelg Beach, and watch the world from the jetty. I did something similar. I had a beach where I’d climb over a clifftop guard rail, curl up in a small sandstone depression in the cliff, and watch the sun set into the waters of Gulf St Vincent.

Jim didn’t write this book for me (or just for me). But I open the front leaf of my copy of Working Class Boy, and I see in Jim’s scrawl

And I am grateful.

Okaaay. Already I want to quote almost every paragraph.

Okaaay. Already I want to quote almost every paragraph.

What if your spouse went missing for seven years then apparently returns – only it’s not him, and this person who claims to be the man you loved appears to have a mysterious, vindictive agenda?

What if your spouse went missing for seven years then apparently returns – only it’s not him, and this person who claims to be the man you loved appears to have a mysterious, vindictive agenda?

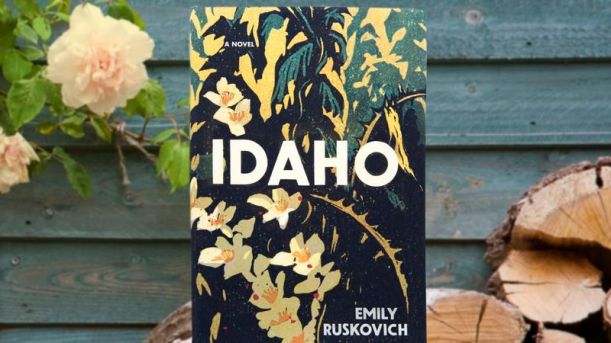

On a mountain-top in rural Idaho, a mother kills her 6 year old, in a seemingly impulsive, reflex action. She “waived her right to a trial, entered a plea of guilty, and, in a hearing that lasted twenty minutes was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole after thirty years. During this hearing, the judge seemed to find her lack of self-regard unsettling, her adamant plea of guilt unusual. He pressured her to give an explanation, but she only said she had committed the murder of her child and she wished to die for it.”

On a mountain-top in rural Idaho, a mother kills her 6 year old, in a seemingly impulsive, reflex action. She “waived her right to a trial, entered a plea of guilty, and, in a hearing that lasted twenty minutes was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole after thirty years. During this hearing, the judge seemed to find her lack of self-regard unsettling, her adamant plea of guilt unusual. He pressured her to give an explanation, but she only said she had committed the murder of her child and she wished to die for it.”

Carina Chocono was losing her mind as a movie critic:

Carina Chocono was losing her mind as a movie critic: As Chocono noted, “Women’s experience in its entirety seemed contained in that remark, not to mention several of the stages of feminist grief: the shock of waking up to the fact that the world does not also belong to you; the shame at having been so naïve as to have thought it did; the indignation, depression, and despair that follow this realization; and, finally, the marshaling of the handy coping mechanisms, compartmentalization, pragmatism, and diminished expectations.”

As Chocono noted, “Women’s experience in its entirety seemed contained in that remark, not to mention several of the stages of feminist grief: the shock of waking up to the fact that the world does not also belong to you; the shame at having been so naïve as to have thought it did; the indignation, depression, and despair that follow this realization; and, finally, the marshaling of the handy coping mechanisms, compartmentalization, pragmatism, and diminished expectations.” Finely etched as a filigree narrative spanning these essays is the story of how Carina Chocono figured out how to save her marriage (Chapter 2 Can This Marriage Be Saved?), be a good mother, be a good writer, and find her way back onto the heroine’s path:

Finely etched as a filigree narrative spanning these essays is the story of how Carina Chocono figured out how to save her marriage (Chapter 2 Can This Marriage Be Saved?), be a good mother, be a good writer, and find her way back onto the heroine’s path: For Chocono, it’s autonomy, agency, and authority. Also, equity and self-expression. To love and to be loved.

For Chocono, it’s autonomy, agency, and authority. Also, equity and self-expression. To love and to be loved.

To me, this, too, did not seem fair. Granted, Ellen was intense. She failed to sufficiently empathise with her husband’s needs. But all she asked was to be loved.

To me, this, too, did not seem fair. Granted, Ellen was intense. She failed to sufficiently empathise with her husband’s needs. But all she asked was to be loved.

Next day, I couldn’t let it rest:

Next day, I couldn’t let it rest:

I’ve just read Paula Hawkins’ Into the Water, and IMO it’s a better and more interesting novel than her bestseller The Girl On The Train.

I’ve just read Paula Hawkins’ Into the Water, and IMO it’s a better and more interesting novel than her bestseller The Girl On The Train.

Ivor Indyk at Giramondo Publishing was one of my lecturers at Sydney Uni 30 years ago, and I see he helped birth Ali Alizadeh’s novel The Last Days of Jeanne D’Arc, which I read last night.

Ivor Indyk at Giramondo Publishing was one of my lecturers at Sydney Uni 30 years ago, and I see he helped birth Ali Alizadeh’s novel The Last Days of Jeanne D’Arc, which I read last night.